Brief #103: big eyes, small hearts

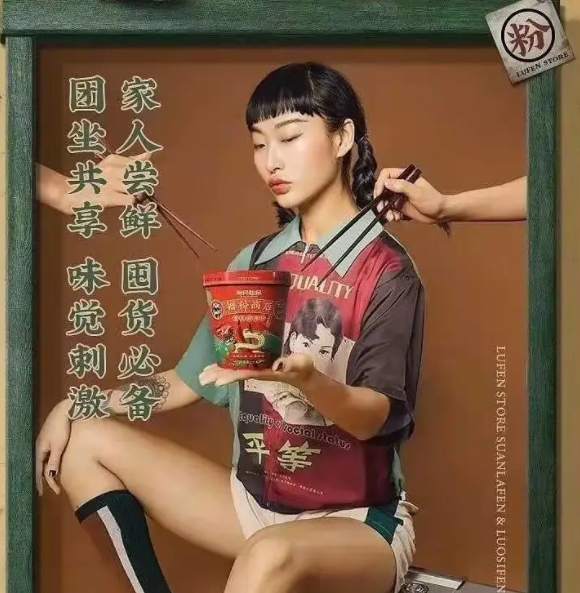

Chinese netizens have been debating about “squinty eyes” (“眯眯眼”) in the last few weeks. The debates centred on a series of advertisement posters from Three Squirrels, a Chinese snack maker, featuring a model with small, narrow eyes.

At the heart of the controversy is the perception by some Chinese netizens that these ads invoked the “slanted eyes” stereotype associated historically with Western racism against Asians. On that basis, they accused Three Squirrels of being “unpatriotic” and “insulting China”.

The Three Squirrels controversy is not an isolated instance. Recently, Mercedes Benz and Dior also came under fire for depicting models with small, narrow eyes in their ads. Chinese animated film I Am What I Am, a story about a boy and his friends chasing their dreams and becoming lion dancers, have come under attack for the eye shape and size of the main characters.

Hypersensitivity

This torrent of outcry underscores China’s political and social environment. Deteriorating relations between China and the US, paranoia about external and internal enemies, Chinese state propaganda, and social media dynamics have made the soil conducive for nationalist discourse.

The Chinese party-state and a portion of the Chinese public have become hypersensitive to perceived insults. This hypersensitivity is hurting China’s relations with the broader world and eroding political tolerance at home.

Yes, the “slanted eyes” stereotype has a long history of association with Western racism against Asians. One prominent example of this is the fictional character Fu Manchu, the personification of the “yellow peril” threat to Western society.

And, indeed, the label “slit eyes” and its associated pulled-eye gesture are highly offensive to Asians even though Western mainstream societies no longer consider Asian eye features as a mark of racial inferiority.

Regardless, today’s racists, like their predecessors, tend to assert their superiority by exaggerating minor variations in human genetics. A slightly more pronounced epicanthic fold becomes “slit-eyed”; a slightly different skin tone becomes “yellow”.

But the Chinese critics are overreacting. They are projecting their nationalist agendas, paranoia and sensibilities onto the aesthetic expressions and intentions of others.

In the case of Three Squirrels, this is a local Chinese company selling to Chinese consumers. Why would it intentionally “insult” its customers by getting into bed with Western racism? It makes no sense whatsoever. A better explanation is that the company was trying to capitalise on international fashion trends.

Some idiots have attacked the model featured in the ads for her looks, labelling her “unpatriotic”. How can the features of one’s eyes be “unpatriotic”? Can the shape of a cloud or the contours of a mountain be “unpatriotic”?

In the eyes of the beholder

Large, double-lid eyes are considered beautiful by the Chinese mainstream. This preference is so strong that millions of young Chinese feel the need to undergo double eyelid surgery every year. Some critics have internalised this preference so deeply that they seem incapable of comprehending that beauty is in the eyes of the beholder: “are you telling me some people find small eyes beautiful? That’s absurd!”

The more sophisticated critics argue that the Three Squirrels controversy underlines the cultural and aesthetic hegemony of the West. They say that China needs to fight western oppression by developing its cultural and aesthetic confidence. Central to this narrative is the idea that bad apples in China are helping the West by self-Orientalising.

But this argument is fatally flawed. First, the standard of beauty varies across time and cultures. For much of China’s dynastic history, tiny feet and small eyes, for example, are considered physically appealing. The mainstream standard of beauty in China today is a distinctively modern product, one heavily influenced by western material culture and aesthetics.

Second, despite calls for emancipation, these critics are having the opposite effect: enforcing conformity of aesthetic expression. Ironically, their aesthetic intolerance is stigmatising their compatriots with small, narrow eyes, the very features that were used historically by Western racists as symbolism for Asian degeneracy.

Moreover, times have changed, aesthetic tastes have shifted, and aesthetic symbols are being repurposed. Small, narrow eyes and other Asian physical features have actually become cool among many Western youngsters due to the global influence of Asian culture.

Yet, some Chinese critics are trapped in the past. Unable to transcend their own prejudices and ignorance, they fail to see the transformative potential of embracing diversity.

A mature society allows space for political and aesthetic pluralism. The Chinese don’t need any more shackles on freedom of expression, including self-imposed ones introduced in the name of liberation.

By Adam Ni