Brief #135: January Politburo Meeting, Asia Power Index

The January Politburo Meeting: A Mystery

No Politburo Meeting was publicly reported for January. This is curious for a number of reasons. For one, the Politburo had routine business to deal with for January. The case is even more curious considering the circumstantial evidence that an unreported Politburo Meeting may have occurred.

My hypothesis is that a Politburo Meeting was indeed held on January 31 and the routine items were bumped off the agenda list by something more important and urgent. And since the Politburo neither considered the routine items nor wanted to make public its considerations on the other item(s), the January 31 Politburo Meeting was not revealed to the public.

I don't know what that "something" could have been — and even if my hypothesis is right, we may not find out for a long time. And even if we do find out, the reason for the January anomaly is more likely to be prosaic rather than high drama at the peak of Chinese politics.

But this case does illustrate the precarious nature of the China-watching enterprise: how little we know and how much we can know from so little.

Politburo Meetings Explained

For background, the Politburo is the highest authority of the Communist Party when Party congresses and Central Committee plenums are not in session. The Politburo usually meets at least once a month. The body's deliberations, views and decisions are made public through official meeting readouts, which are published by state media Xinhua on the same day and carried in the next day's People's Daily, the official newspaper of the Central Committee.

There are different types of Politburo gatherings, but for our purpose, we are only interested in "Politburo Meetings" (政治局会议), which are gatherings of the body to deal with formal business. Another occasion on which the Politburo gathers is its study session, where experts are usually invited to give presentations to China's top leaders on specific topics, such as AI, financial systems and archaeology.

Not all Politburo Meetings are made known to the public; some come to light only years after the fact, usually revealed when official documents or witness accounts reference these meetings.

The Case

With this background, let's consider the evidence for my hypothesis.

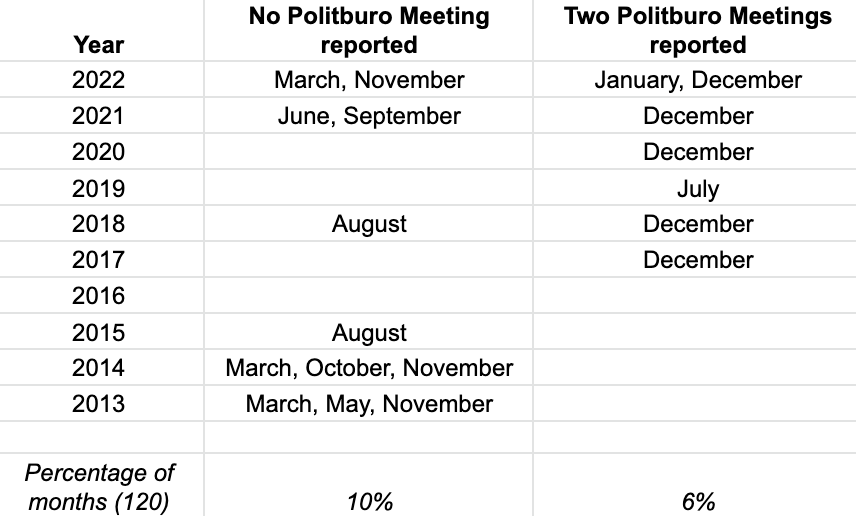

First, it's unusual not to have a Politburo Meeting publicly reported in any given month. From 2013 through 2022 (120 months in total), there were 108 months (90 per cent) for which one or more Politburo Meetings were reported and only 12 months (10 per cent) for which no Politburo Meetings were reported.

The table below shows the months and years in the period for which zero or two Politburo Meetings were reported. The rest had one reported Politburo Meeting, and there was no incidence where more than two Politburo Meetings were reported in a month.

Second, while it is unusual not to have a Politburo Meeting publicly reported in any given month, it is even more unusual for one not to be reported for January of any given year. In fact, this has not happened under the Xi Jinping Administration (November 2012 to present) until this point. Under the Hu-Wen Administration (November 2002-March 2013), this happened in 2004, 2011 and 2012.

Is there a particular reason why it is so unusual not to have a publicly reported Politburo Meeting in January? This leads to my third point.

Third, the Politburo has routine agenda items to deal with every January, making skipping or deferring a meeting less likely.

Due to its seasonal and cyclical nature, there is some predictability to the Politburo monthly agenda. For example, the December Politburo Meetings focus on economic policy for the next year, and the February Politburo Meetings examine that year's draft Government Work Report, which the State Council later would submit to the National people's Congress.

A new routine agenda item was introduced to the Politburo's January agenda in 2015: reports from Party groups of top-level state organs. In 2016, the work report of the Central Secretariat was added to that bundle of reports for deliberation at the January Politburo Meeting, and this agenda item has since become a routine one:

"deliberating the Consolidated Status Report by the Standing Committee of the Central Political Bureau on Hearing and Studying the Reports on the Work of the Party Groups of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, the State Council, the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, the Supreme People's Court and the Supreme People's Procuratorate and the Work Report of the Central Secretariat."

审议《中央政治局常委会听取和研究全国人大常委会、国务院、全国政协、最高人民法院、最高人民检察院党组工作汇报和中央书记处工作报告的综合情况报告》

Sorry for the tortuous title, but what essentially happens is that the Party groups in the top-level state organs along with the Central Secretariat would submit their annual work report to the Politburo Standing Committee, and the latter would examine them and write a Consolidated Status Report for deliberation by the full Politburo.

The content of this agenda item is only tangential to our line of argument; what is important is that this item has become a routine agenda item: since 2016, the annual Consolidated Status Report has been considered every year at the January Politburo Meeting (except, of course, for 2023).

The data says that Politburo Meetings are more likely to be reported in any given month for which there are routine agenda items. As the table above shows, in the years from 2013 through 2022, January, February and December of all years recorded at least one reported Politburo Meeting. The rationale is institutive: the Politburo has routine business to deal with in these months.

In some cases, the Politburo's deliberation of routine items is part of a larger bureaucratic process with a timetable. Take the Government Work Report for example. The draft report must first be endorsed by the Politburo before the State Council can submit it to the National People's Congress during the latter's annual session (usually in March). This means that a Politburo Meeting will need to be convened to consider the report in February.

Another example is economic policy work. The December Politburo Meetings sets the direction for China's economic policy priorities for the next year. Later that month, China's economic policymakers would gather at the annual Central Economic Work Conference to flesh out policy details in line with the views of the Politburo.

Fourth, the Politburo members (or at least their advisers) and staff at the Central Secretariat that support the operations of the Politburo must have known that by not dealing with routine business in January, they would have a jam-packed February agenda, including:

- reports from Party groups of top-level state organs and the Central secretariat (routine item for January, likely deferred to February);

- Central-dispatched inspection tours (routine item for January or February);

- draft Government Work Report (routine item for February);

- Second Plenum of the Central Committee (expected item for February)

This list would be even longer with ad hoc (non-routine) items, such as new Party regulations and directives. From 2013 through 2022, there was at least one ad hoc item at the January or February Politburo Meetings every year except for 2016.

To digress, we should expect the next publicly reported Politburo Meeting to be around February 18, the latest February 24. The reason is that the Central Committee will likely convene its Second Plenum in late February and past practice suggests that the Politburo will announce the dates for the event a few days prior.

If no Politburo Meeting had been publicly reported by the end of February, something strange would have happened. My assumption is that there will be at least one publicly reported Politburo Meeting for February.

Back to the mystery of the January Politburo Meeting...

Finally, the Politburo held a study session on the afternoon of January 31, which suggests that a Politburo Meeting may have been held in the morning. Politburo study sessions are usually held on the same day as a Politburo Meeting, presumably for logistical reasons (not easy to get China's top leaders in one place).

From 2013 through 2022, the Politburo held 83 study sessions out of which 75 (90 per cent) occurred on a day for which a Politburo Meeting was recorded. I suspect the portion would be higher if the unreported Politburo Meeting were taken into account (although admittedly, we lack the data to confirm this).

All of the above leads me to believe that an un-publicly-reported Politburo Meeting was held on January 31 at which routine business was not all dealt with. And routine business was not all dealt with probably because something more important and urgent demanded the Politburo's attention.

The explanation for the January anomaly may well be prosaic and bureaucratic — we don't know. But the case does highlight the precariousness of the China-watching enterprise...

China-watching: A Precarious Enterprise

In the public domain, we know little about what is currently happening at the apex of China's political and policy processes. This is because the Party guards information from the public's prying eyes and does not have a tradition of transparency.

The opacity of China's political system and limited information on contemporary elite politics and decision-making calls us to be more circumspect about our predictions. It also begs us to be more responsive in updating our models and assumptions to changing facts.

But despite the precariousness, there is no doubt that we can still deduce a surprising amount of useful information and insights from the trickle flowing out of Zhongnanhai. To do this, we need to understand the political ecology, bureaucratic processes, history, rituals, and norms of the Party-state.

China-watching is precarious but not hopeless.

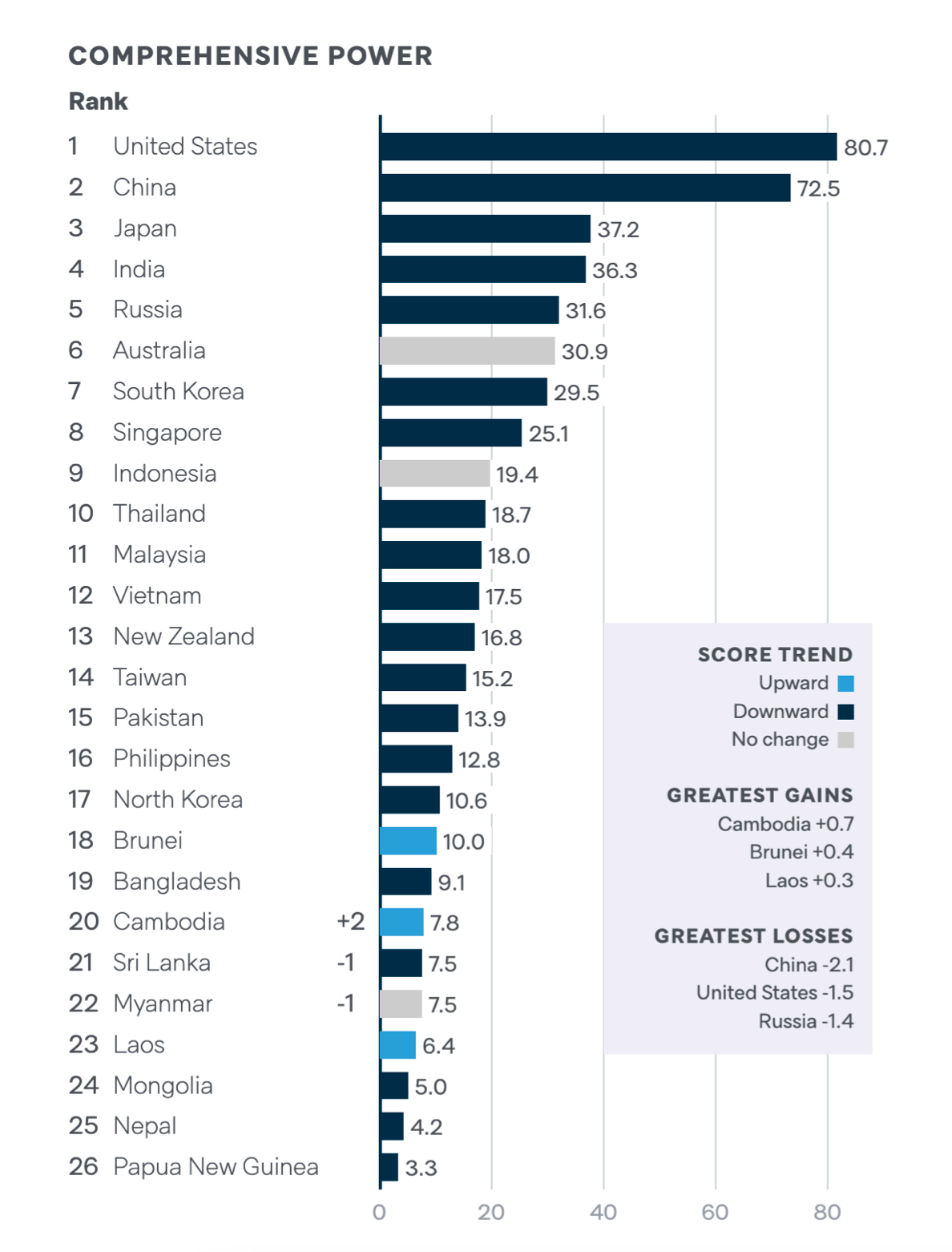

2023 Asia Power Index

The Lowy Institute’s annual Asia Power Index ranks the relative power of states in Asia by measuring their resources and influence. The 2023 edition, published last Monday (February 6), has two China-related key findings.

China Findings

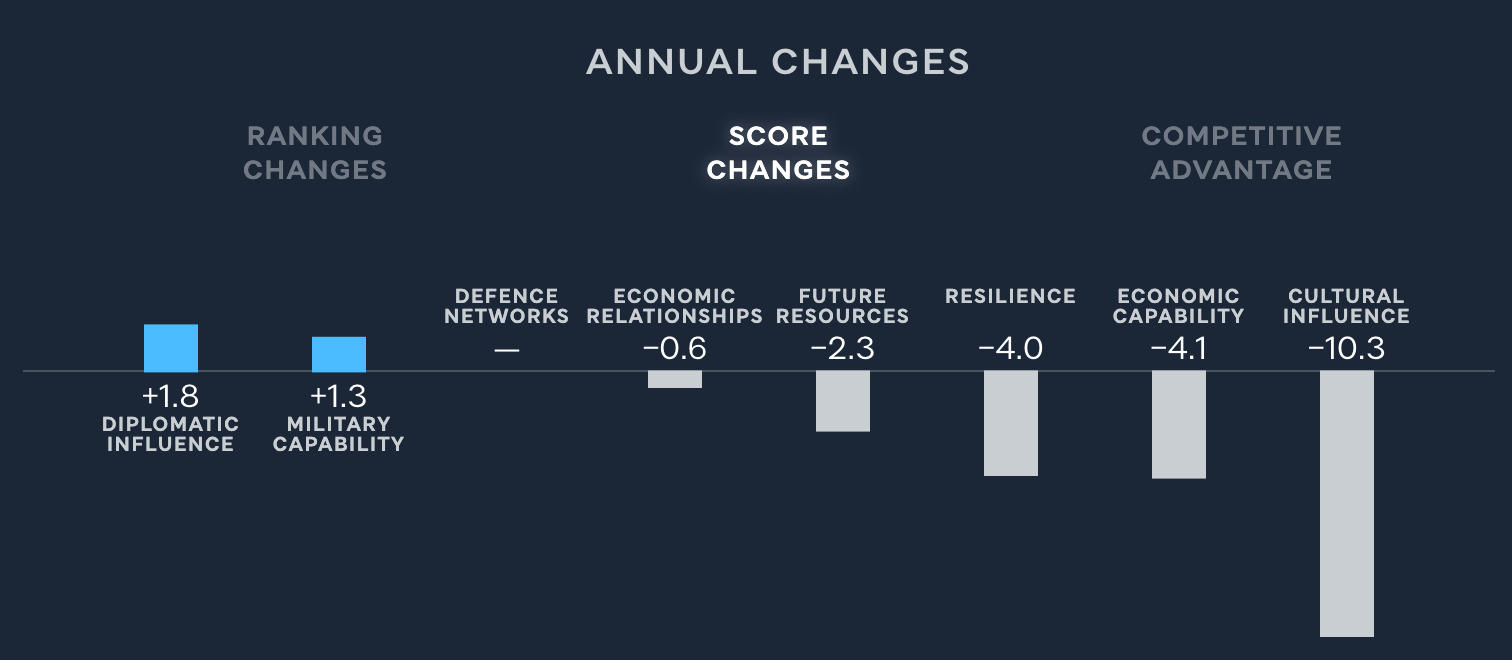

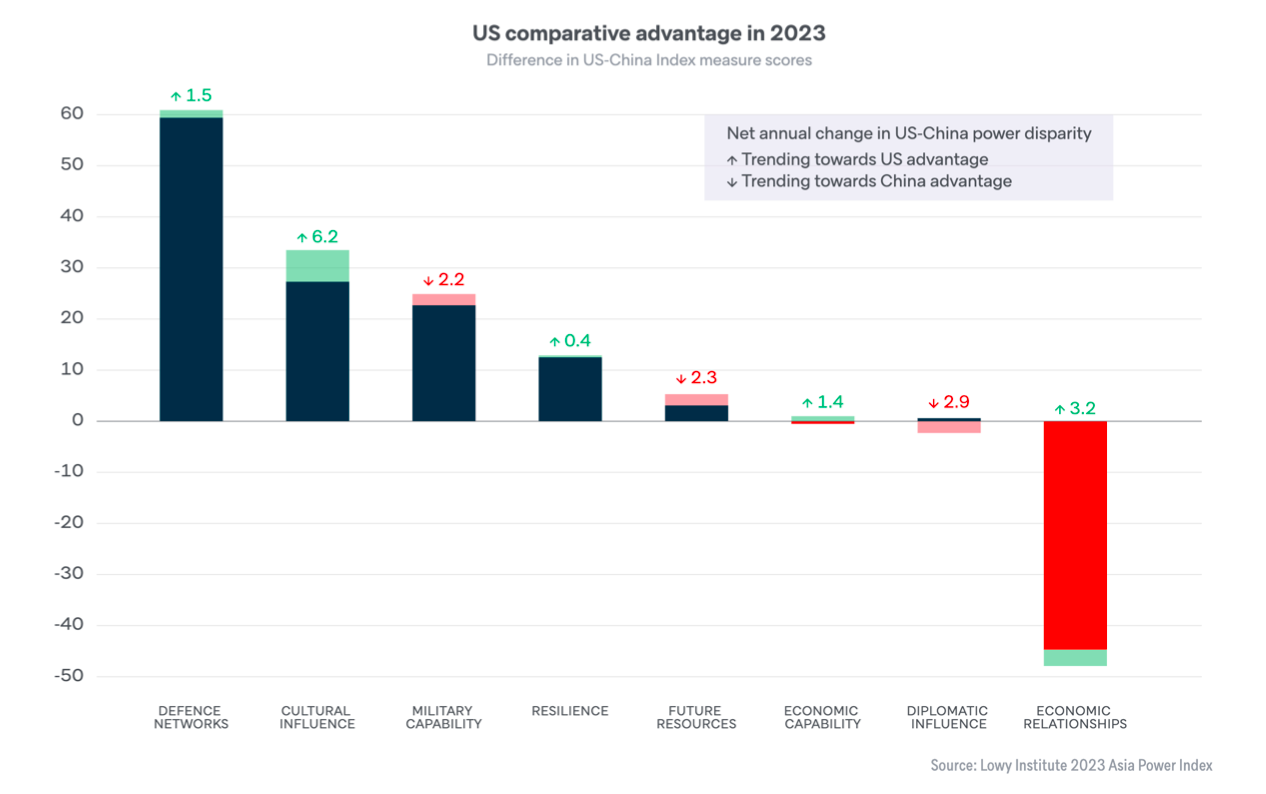

First, China’s standing fell substantially in 2022 due to lower economic capability and cultural influence, reflecting the negative effects of China's self-imposed COVID isolation on economic connectivity, foreign investment (both inward and outward) and people-to-people exchanges.

Second, due to China's setback, the United States remains on top in terms of comprehensive national power:

2022 was an annus horribilis for China, and the drop in its national power reflects this. With the COVID and travel restrictions lifted, China's links with the world will normalise, removing some impediments to building economic and cultural power.

Geopolitical Trends

Beyond annual fluctuations, data from the last five years of the Index points to broader geopolitical trends in Asia.