Brief #96: history resolution, rally round the flag, Wang Liqiang, beauty standards

1. History resolution

At the recent 6th Plenum, the Party Central Committee adopted a resolution on history. The Party made this document public last Tuesday (November 16). We told you that the 6th Plenum communiqué lionised Xi and whitewashed history. The text of the resolution confirms this assessment.

The resolution praises the Party’s achievements, downplays its failings, and hides its crimes. In constructing a linear and distorted version of history in the service of power, it tells you three things:

1. History has proved the Party to be “great, glorious, and correct”.

2. The Party’s laudable past foretells a bright future for China under its leadership.

3. Xi Jinping is uniquely qualified to lead the Party and the Chinese people towards that bright future.

At 37,000 Chinese characters, the resolution is long. Below is a series of illustrations to help you visualise what the document is really about.

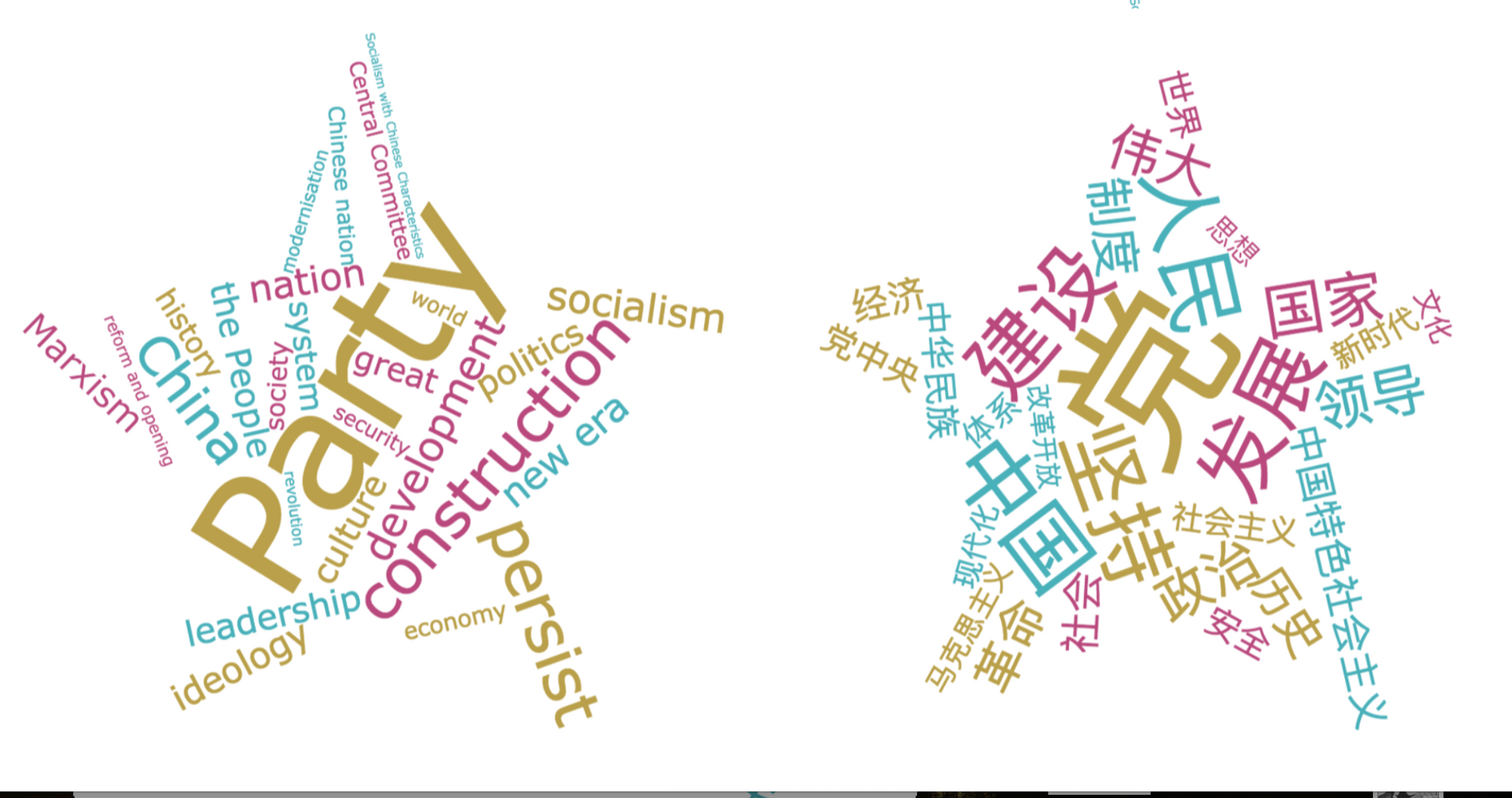

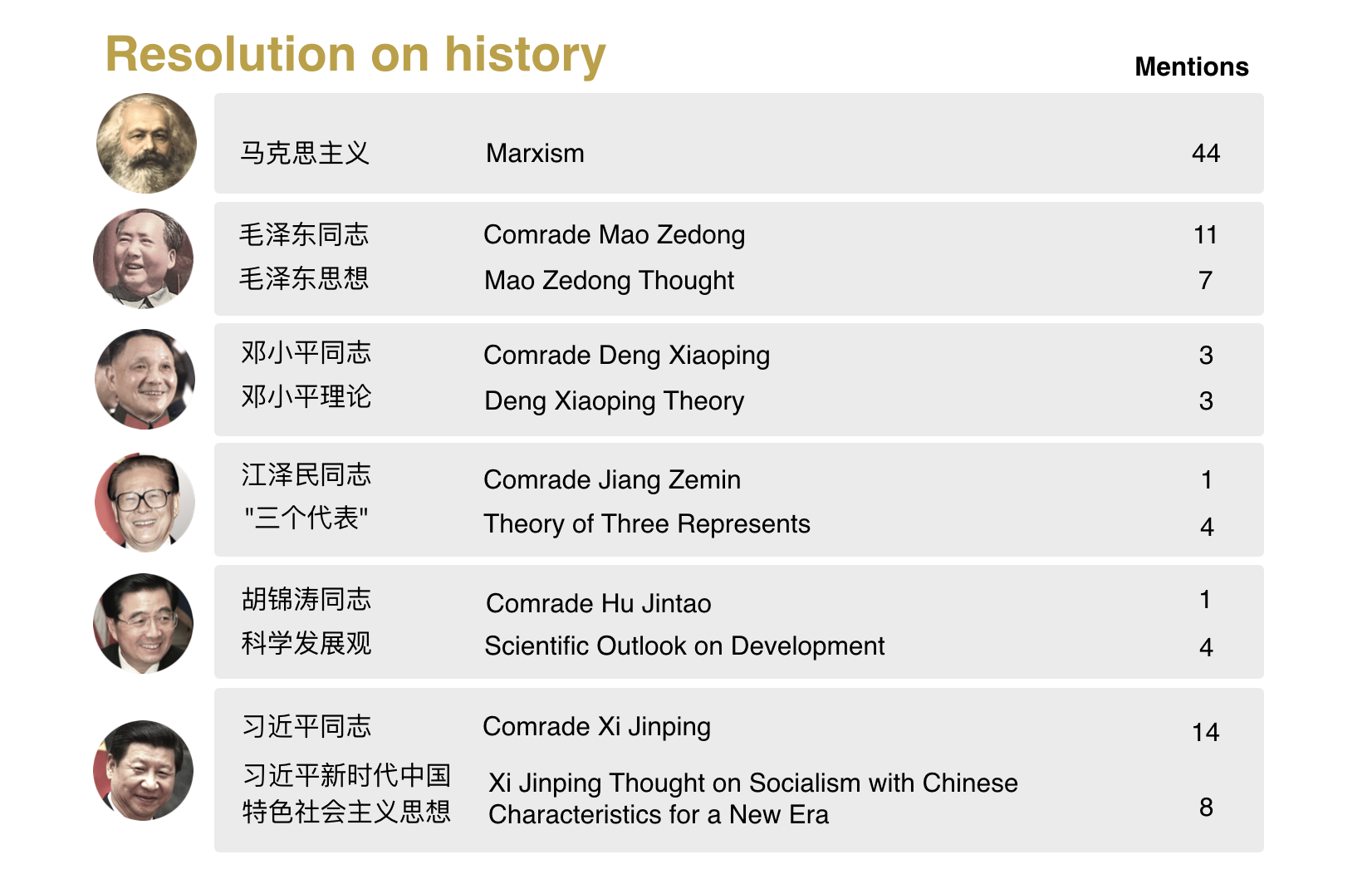

First up, a wordcloud of the most frequently used terms:

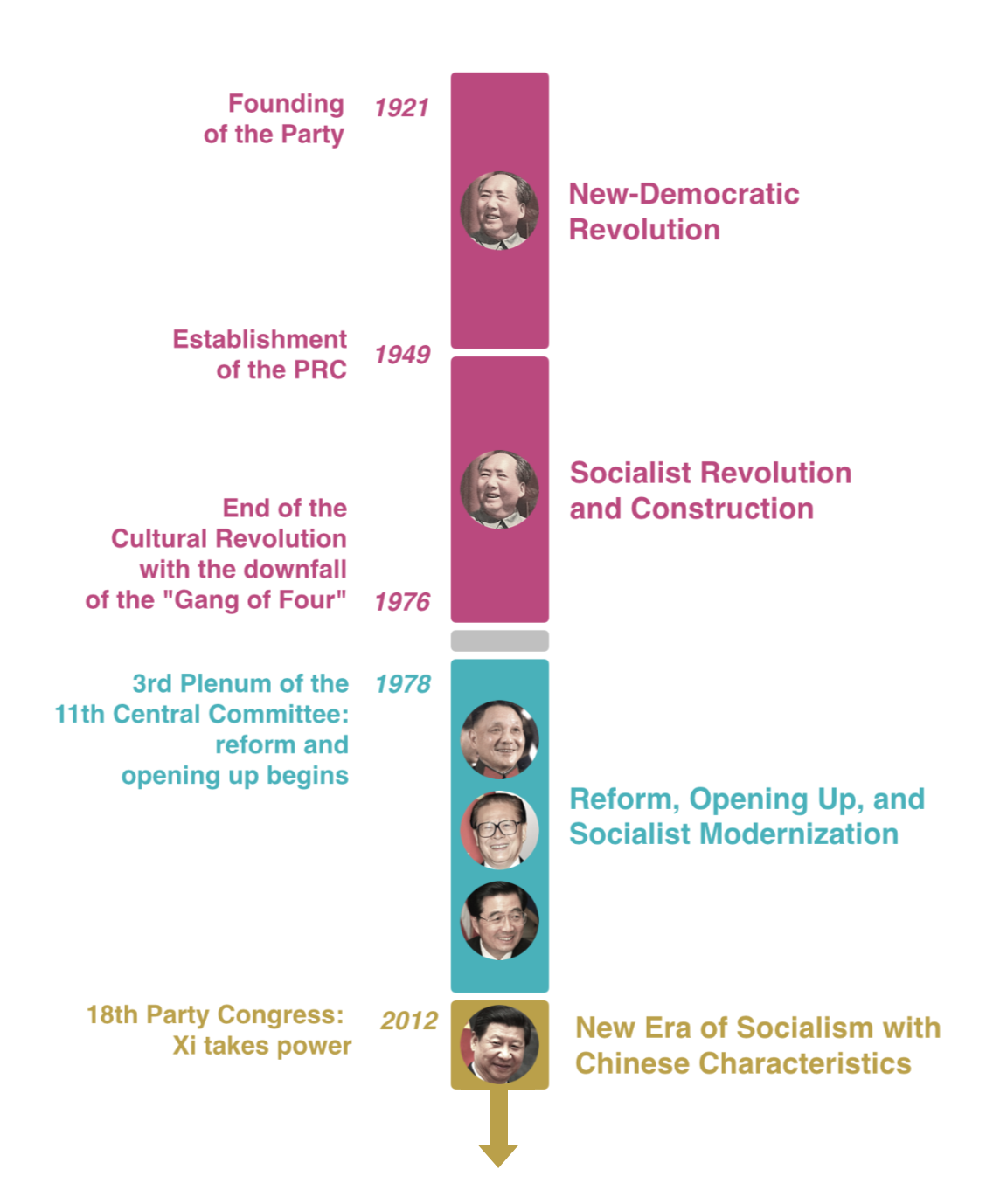

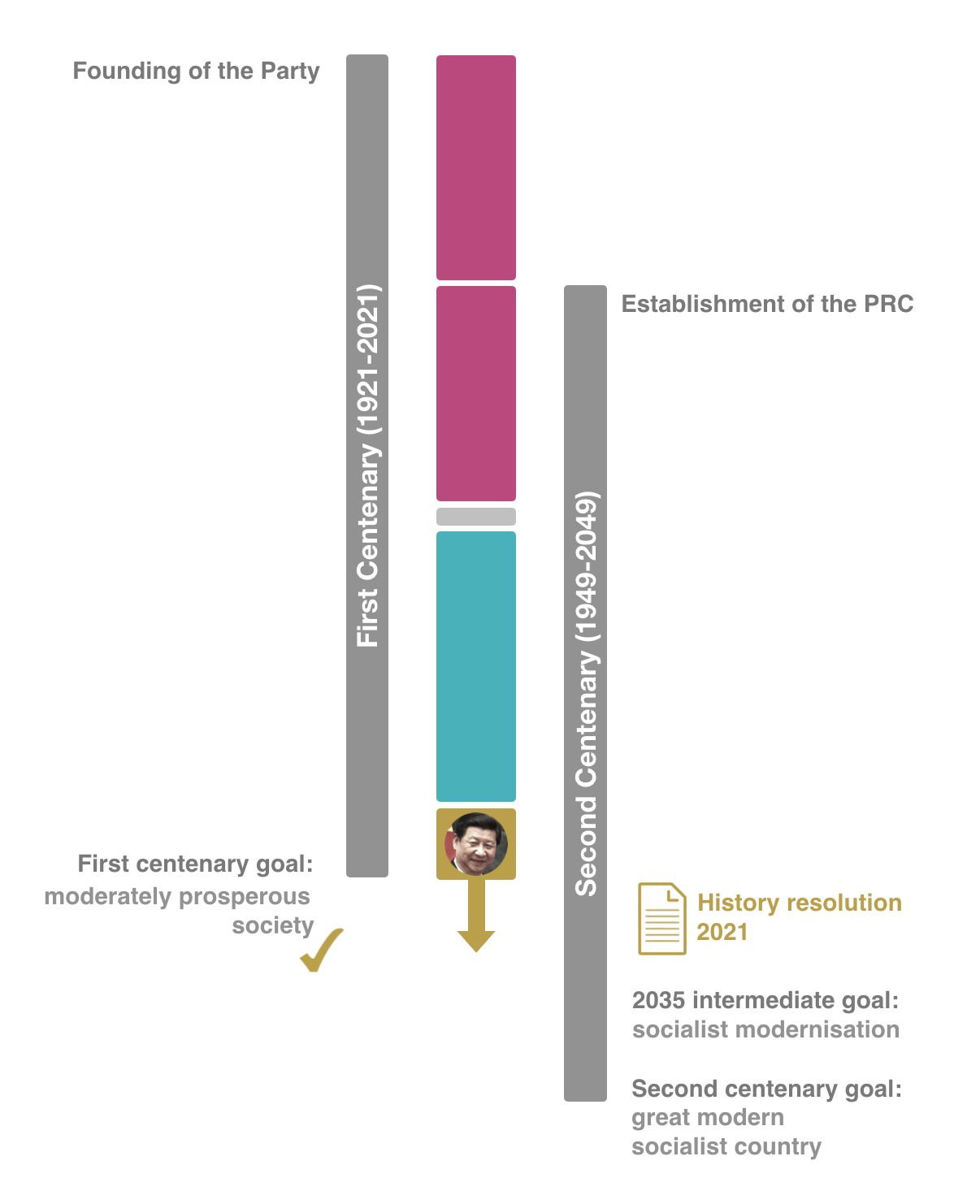

The periodisation of Party history according to the resolution:

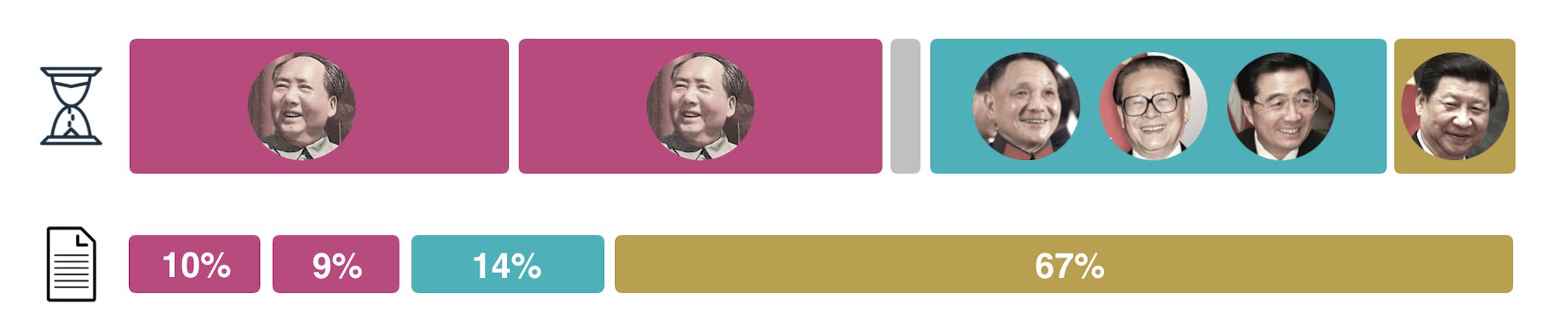

Xi is the star of the show. In the resolution, 67 per cent of words used for assessing the different periods were expended on Xi’s new era.

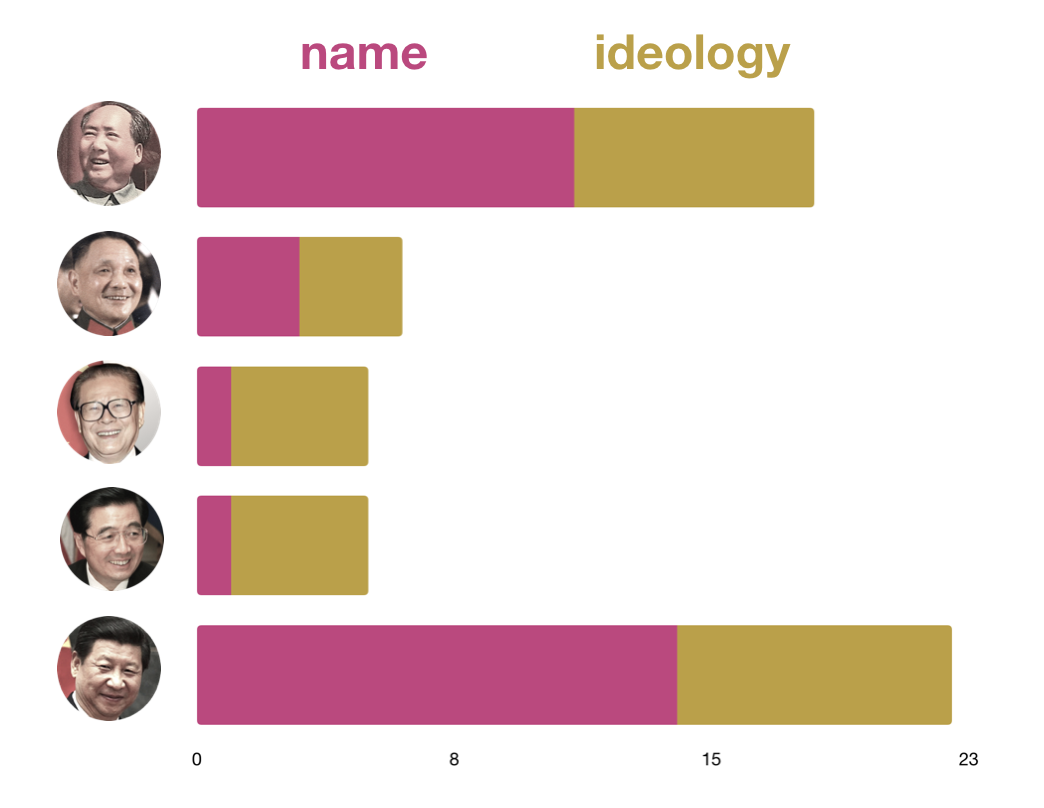

The resolution mentioned Xi’s name more times than any of his predecessors. The same goes for Xi’s ideology.

The resolution mentioned Marxism more times than Xi’s ideology. Marxism is considered the guiding light in CCP ideology, so this is not surprising.

Here is how the two centenary goals fit into the official periodisation of Party history:

The resolution reserves a special place for the five “chief representatives” of communists of their generations. These are the winners of political struggles. They were rewarded with the power to (re)write Party history.

Xi is rewriting the history of the past for political expediency. Future Party leaders will do the same: they will (re)write the history of Xi’s vaunted new era.

2. Rally round the flag

It’s not yet election season in Australia, but the major parties are already in campaign mode. On foreign policy, there is usually a “bipartisan consensus,” as political parties want to avoid the appearance that the country is divided in the face of “external” threats.

However, the need for “bipartisan consensus” gives the incumbent an advantage. The ruling party can use foreign policy as an “election wedge.” But the opposition must think twice before criticising the government’s foreign policies, lest they be perceived as helping foreigners to “sledge Australia”.

In a democracy, public policies are always contestable. It is the job of opposition parties to be critical of government policies where they see fit. Yet when it comes to foreign policy, the political party in power can portray itself as representative of the state and appeal to “national unity” in the face of criticisms. The incumbent can even accuse the opposition of “backing a foreign government”.

Can you imagine an appeal to “national unity” to deflect debate on income taxes? Or to accuse the opposition of “backing Norway” if they advocate for free university education? There would be no democracy if we must all take the same position on public policy. Further, “consensus” does not guarantee good policy outcomes.

Yet, in the current climate, even something as innocuous as stating that the bilateral relationship with China is important, which is common sense in the region, can be deemed “appeasement” or “capitulation”. While the US Government stresses that competition need not lead to conflict, the Australian Government is again talking up the prospect of war.

Elena Collinson lists three dangers with the current discourse:

First, the charge of ‘disloyalty’ which is virtually slapped on anyone questioning the government line subverts an important pillar of Australian democracy — implied freedom of political communication is a crucial part of the system of representative and responsible government. For cabinet ministers to suggest otherwise sets a dangerous precedent.

Second, muzzling discourse, the promulgation of one perspective at the expense of all others, weakens policymaking. This debate is one that needs more voices, more allowances for flexibility in thinking and in action if the strongest policy settling point is to be reached.

Third, the specific type of epithets being used help pave the way for racial prejudice, already on the rise, and further marginalisation of Chinese-Australians.

These dangers are tricky to tackle. They go hand-in-hand with the trend of politicians appealing to populist nationalism, both in Australia and beyond. People are much more engaged and willing to mobilise when there is an imminent external threat.

3. Wang Liqiang

Two years ago, right after we launched China Neican, the Wang Liqiang 王立强 case exploded in the public consciousness.

A reminder of what happened: On November 23, 2019, Australian media broke the story of the defection of an alleged PRC intelligence operative, Mr Wang Liqiang. Wang claimed that he was involved in the Causeway kidnappings in late 2015, the infiltration of Hong Kong student organisations, and information operations in both Hong Kong and Taiwan for the CCP.

Two days later, we wrote on this fledgling newsletter that:

Many of Mr Wang’s public claims are unsupported or uncorroborated based on the available evidence thus far. Some of his claims are not true, and some of his statements detract from his credibility. Circumstantial evidence has raised additional questions.

Our scepticism of Wang’s claims propelled us to national media attention. However, most of the attention was on the supposed intelligence goldmine offered by Wang. In general, sceptical voices were drowned out by a thrilling spy drama.

In the face of scepticism, some alleged that Wang was a “cutout”, not a “spy”, though it belies belief that a “cutout” would have access to so much intelligence — and the 60 Minutes expose clearly labelled him a “spy”.

The saga continued with authorities in Taiwan investigating the alleged spies outed by Wang. Some saw this investigation as a vindication that Wang was the real deal.

However, this week it emerged that these alleged outed spies would not be charged after all due to a lack of evidence. This outcome is odd, as you’d expect the information collected from Wang’s intelligence goldmine would have helped the Taiwanese authority’s case.

But does the drop of charges or the lack of intelligence from Wang matter? After all, in most people’s minds, the Wang saga has cemented and confirmed the oft-repeated narrative that China is an imminent threat to Australia’s national security.

Indeed it doesn’t matter if the story is later debunked — the sensations are produced, people’s minds are made up. Retractions generally have less impact than the original story. In this case, there is not even a follow-up to Wang’s claims by Nine/Fairfax. Should the media have reported the story with so many holes? Why were the holes in Wang’s account not adequately investigated by the investigative journalists? These holes should be evident to anyone who has rudimentary knowledge of national security. One thing appears certain: no one involved with this saga will face serious repercussions.

4. Beauty standards

There is another controversy on the Chinese internet regarding the standard of beauty. Chen Man 陈漫, a top Chinese fashion photographer, was heavily criticised for her work for Dior. Chen apologised after the outrage.

For background, there have been regular debates online about how Westerners portray beauty in Chinese people. Here, the criticism is that even though Chen is Chinese, she produces work for the Western gaze.

In China, being slim, pale and having big eyes with “double eyelids” are traits commonly associated with beauty in women.

Yet, people in China found that the popular portrayal in Western media of Chinese women is quite different. This portrayal has led to accusations that the Western media is deliberately “orientalising” or “caricaturing” Chinese women, including by emphasising “slanty eyes”. Many short videos were also made about how Western men prefer “ugly” Asian women.

Amidst the accusations that Chen’s portrayal is pandering to the Western taste and is racist, racist comments have also emerged about people who look different from the standard notion of Han Chinese — that they don’t “look Chinese” enough.

Fashion photography is on another level. Fashion photography often aims to stand out and emphasise differences rather than striving for a common notion of beauty.

We’re not well-versed in the history of art and fashion to understand the complexities here. But to us, individuals have different standards of beauty, shaped by their environment. We should embrace differences rather than strive for uniformity in beauty.

By Yun Jiang and Adam Ni

This brief is made possible by the support of the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University.