Brief #83: common prosperity, AfPak, online privacy

1. Common prosperity

As readers know, the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission, China’s highest economic decision-making body, held a meeting to discuss “common prosperity” 共同富裕 (the Chinese term is also the literal translation of “common-wealth”, but Commonwealth means something quite different from common-wealth nowadays).

You can find Adam’s take on the topic and his translation of the readout.

Even though China is ostensibly a “socialist” country working towards “Communism”, inequality in China is worse than in many “capitalist” countries, especially when compared to social democratic countries such as Norway or Finland.

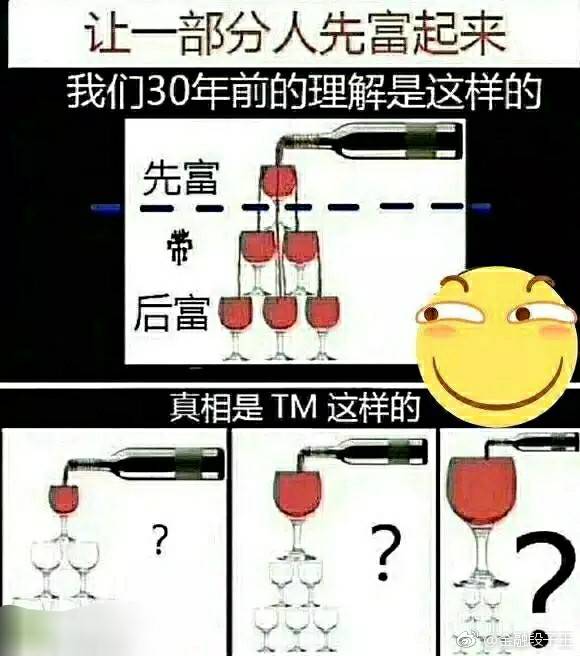

Deng’s motto “let some people/regions get rich first” 让一部分人、一部分地区先富起来 was followed by “lead and help others to achieve common prosperity” 带动和帮助其他地区、其他的人,逐步达到共同富裕. This sounds like “trickle-down economics” as practised in the US.

Under this idea, some people got extravagantly rich. While the poor also got richer (China proclaimed the elimination of absolute poverty), the disparity between rich and poor has grown. But more than that, some poor people now believe the game is stacked against them, and have become nostalgic for the “real Communism” before Deng.

Yuen Yuen Ang, a professor of China’s political economy, calls China since Deng “China’s Gilded Age”. I agree with her comparison:

The Gilded Age, which began in the 1870s, was an era of crony capitalism as well as extraordinary growth and transformation. Following the devastation of the Civil War, the United States rebuilt and boomed. Millions of farmers moved from fields to factories, infrastructure opened up long-distance commerce, new technology spawned new industries, and unregulated capital flowed freely. In the process, swashbuckling entrepreneurs who seized on the right opportunities at the right time—Stanford, J. P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller—amassed titanic levels of wealth, while a new working class earned only a pittance in wages. Politicians colluded with tycoons, and speculators manipulated markets.

It is also an image reminiscent of Dickensian England (the same time that Marx was in England), and precisely the sort of image portrayed by the CCP until the 70s of what capitalist societies are like.

Highly visible hyper-inequality is generally detrimental to regime stability, or even economic growth. Now that the cake in China has gotten bigger, perhaps it is time to think about how to divide it. And since “trickle-down economics” does not work, the government needs to play a crucial role in redistribution.

Marxists predicted that the Communist revolution would only occur after industrialisation, yet the Chinese Communist Party took power when China was still largely agrarian. Now that China has become an industrial power, the government, like other capitalist governments, should start to implement more progressive policies to stave off a potential revolution.

However, there is a difference with China compared to other “capitalist” countries — China is not a democracy. It remains to be seen whether the CCP can pull off this feat using top-down tactics without significant unintended consequences. As power and wealth are so intertwined, is it possible to have such a high degree of concentration of power with dispersion of wealth?

2. Stability and security in AfPak

A suicide attack targeting a vehicle carrying Chinese nationals occurred near Gwadar Port. The Gwadar Port is the flagship project of China’s BRI in Pakistan. And Pakistan is probably China’s closest partner right now — an “all-weather friend” and an “iron brother”.

China’s BRI projects operate in some unstable regions of the world. But that’s not to say Chinese companies prefer instability. Most of China’s investment still flows to more stable countries such as the United States and European countries. Western companies, especially resource companies, also operate in many unstable regions. Companies of course prefer stable governments, and generally require a higher rate of return for projects in riskier areas.

The Chinese Government no doubt also prefers to deal with stable governments, whether authoritarian or democratic. This is why China is willing to work with the Taliban in Afghanistan, even though the group killed 11 Chinese workers in 2004. As long as the Taliban can bring some stability to the region, it is positive for China’s interests. Similarly, China was willing to work with the military junta in Myanmar, even though it actually preferred the democratically-elected NLD.

Private companies operating in unstable regions generally rely on private security, including private military companies (such as the notorious Blackwater). With the growth of BRI in unstable regions, China’s private security industry is also expanding.

However, in China’s case, the line between private and the state can be easily blurred. This is demonstrated by the case of Huawei. And with expanding Chinese interests, including business interests and even tourists, in Central Asia and the Middle East, there will be strong popular pressure for the Chinese Government to do more to protect these interests. After all, the Chinese Government has raised this expectation itself, with films like Wolf Warrior and Operation Red Sea.

3. Personal information protection

Following the Data Security Law, the National People’s Congress recently adopted the Personal Information Protect Law [China Law Translate, DigiChina]. The law deals with the collection and processing of personal information by private companies, similar to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation.

This is a significant step forward for online privacy in China. Contrary to popular perceptions, people in China do care about privacy. But like consumers everywhere, it’s always about the trade-off, for example between privacy and convenience, and these days, between privacy and public health.

Note that the law mostly regulates the exchange of information between individuals and companies, not between the state and individuals (although there is a section on the processing of personal information by state organs, “legally prescribed duties” can be very broad). The Data Security Law, on the other hand, has more potential national security implications. Of course, if there was a conflict between national security and privacy, we expect national security to always prevail — this is not limited to China.

Adam’s Corner

Hey everyone, two items from me this week. First, I translated the new joint decision by the Central Commitee and the State Council on fertility policy. China’s population fertility level has been alarmingly low for some time, and Beijing wants to change that. By making childbearing and childrearing less burdensome and costly, it hopes people will become more inclined to have (more) kids. I’m not sure if the added incentives from government policy will be enough to counteract the trends that have been pushing fertility lower, including new social norms, gender roles and relations, and patterns of personal preferences.

Second, I translated the official readout of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission meeting last Tuesday (August 17), which focused on the idea of “common prosperity”. This is actually really important. Essentially, this is about trying to redistributing the cake now that the cake is much bigger than before. If you are interested in how the Chinese leadership perceives the nexus between inequality, economic development, income (re)distribution, and financial risks, then do read my introduction and translation.

Forecast says that there will be more rain in the next few days here in Saxony than an average summer! I think I will stay indoors and drink the pork bone soup I’ve been simmering for the last day or so. Hope it’s sunny wherever you are (unless you are experiencing drought, of course)!

Neican Brief is made possible by the support of the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University.