Brief #10: death of Li Wenliang, censorship & propaganda

Hi all, please join us in Sydney this upcoming Friday (Valentine’s Day) 6pm at Assembly Bar (488 Kent Street). Only five days to go! RSPV not required, but would be nice so we have a rough idea of the numbers.

We dedicate this issue to Dr Li Wenliang who passed away this week. He is a victim of the coronavirus outbreak, one of the hundreds that have lost their lives since December.

- Yun and Adam

Death of the Doctor

By far the biggest China news this week is the tragic death of 34-year-old Li Wenliang 李文亮, a Wuhan doctor who was admonished by the authorities, along with seven others, for spreading “rumours” about the coronavirus in late December.

All Dr Li did was to warn his friends in a private WeChat group to take precautions against the new disease. Wuhan police took him in, censured him and made him sign a statement promising to stop making claims about the disease. This is a classic case of authorities overriding individual liberties and transparency in the name of social stability.

The censure and censoring of Dr Li triggered massive public backslash. His death triggered an even bigger tsunami of public anger and frustration. We have NEVER seen such an outpouring of emotion on Chinese social media, and much of it was directed against the Chinese authorities.

Below is the warning letter that Dr Li was forced to sign.

Qin Chen at Inkstone translated some of it:

“The law enforcement agency wants you to cooperate, listen to the police, and stop your illegal behavior. Can you do that?”

“I can,” Li wrote under the question.

“If you insist on your views, refuse to repent and continue the illegal activity, you will be punished by the law. Do you understand?”

“I understand,” Li answered.

(bold emphasis added)

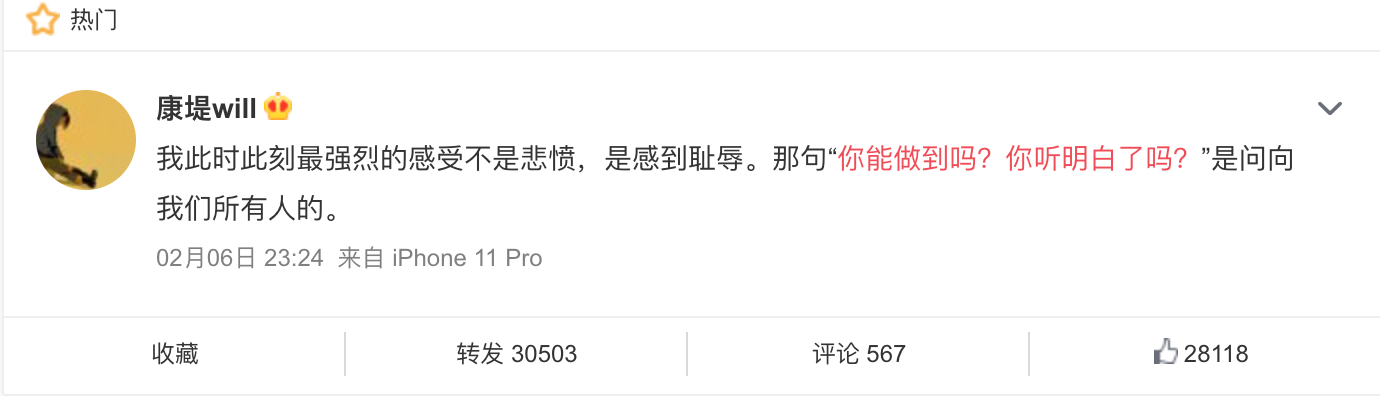

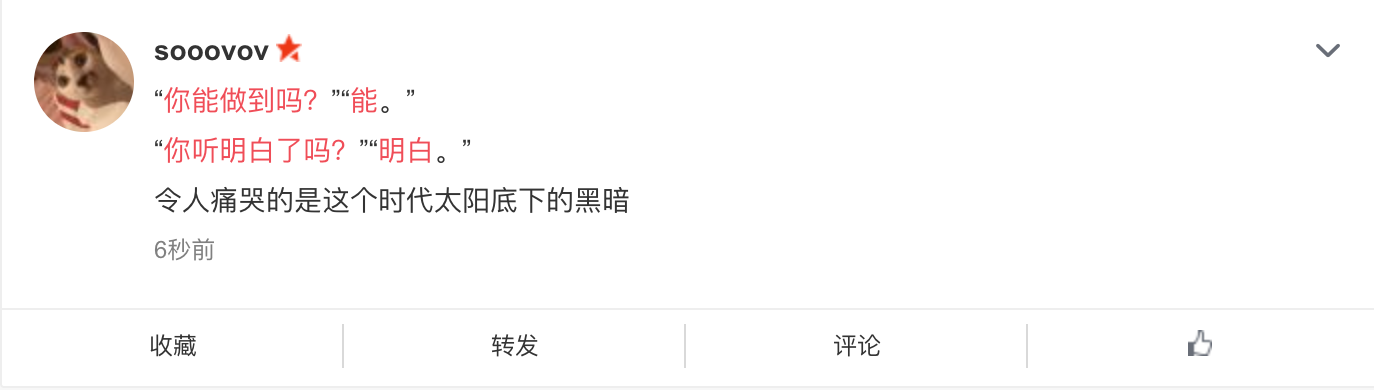

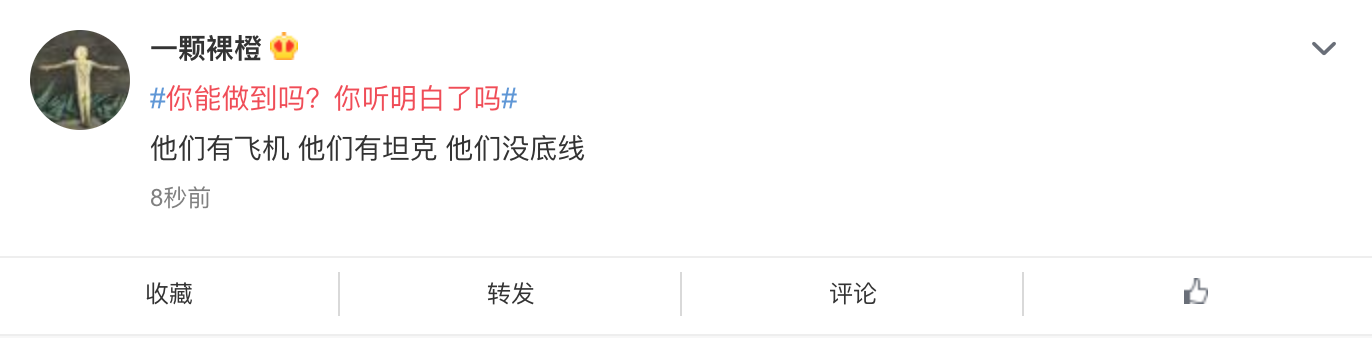

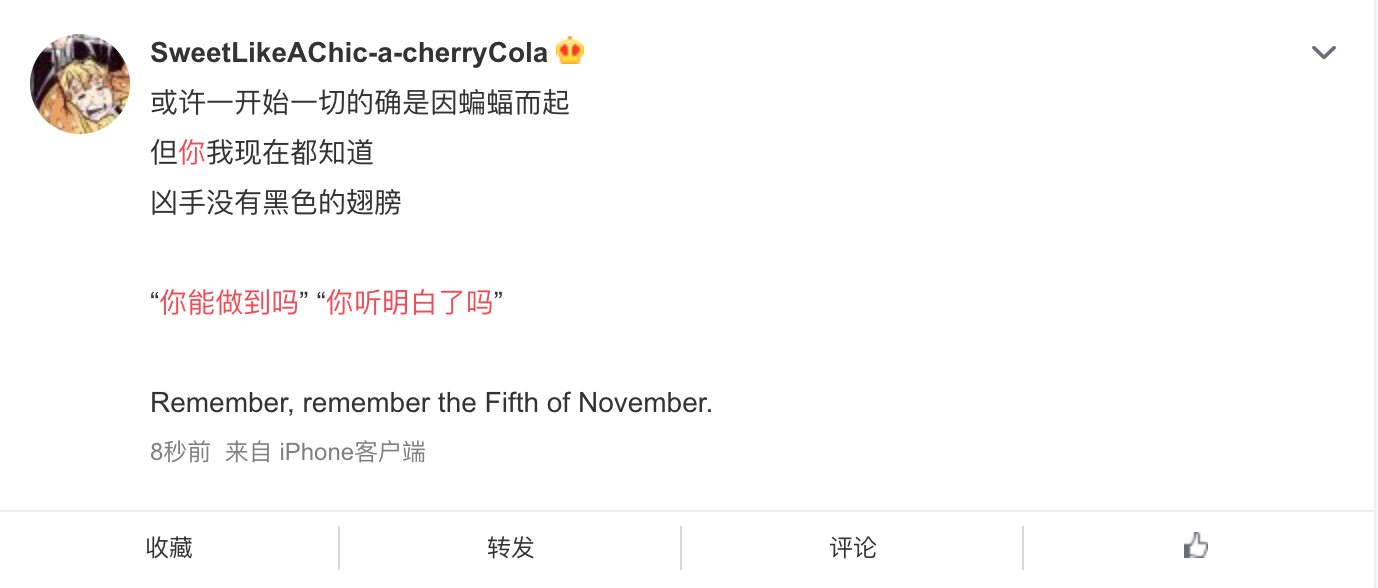

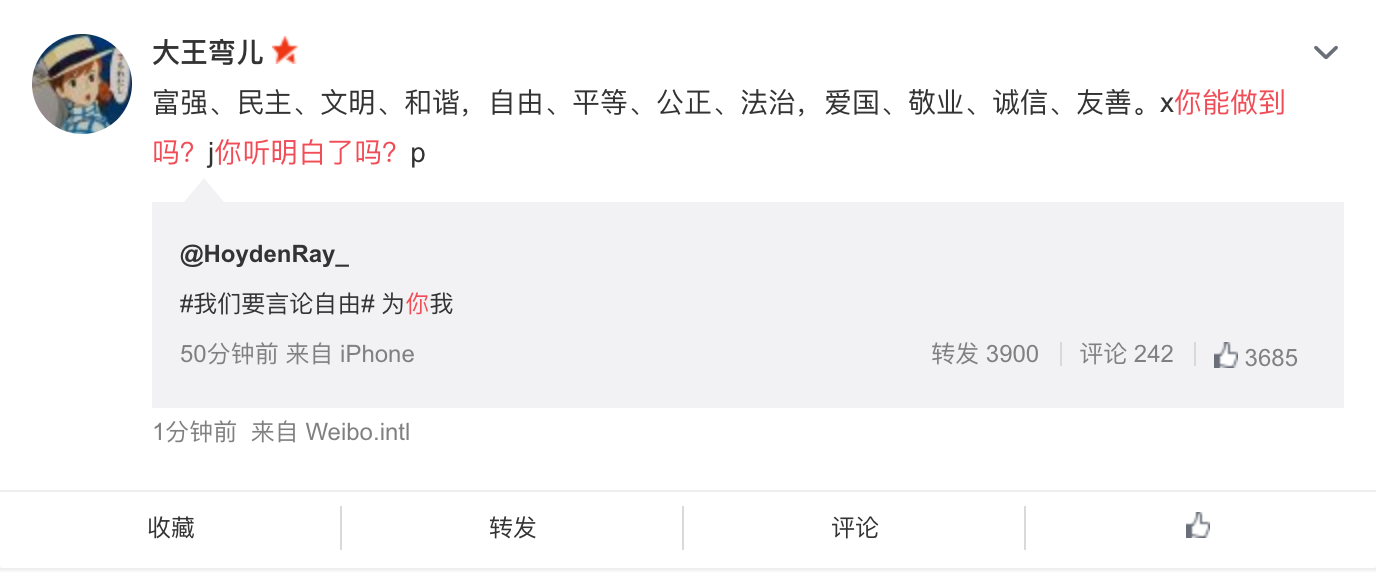

“Can you do that? Do you understand?” 你能做到吗?你听明白了吗?became an instant meme on the Chinese internet following the death of Dr Li. The hashtag has since been banned, and censors have been working non-stop to delete posts. But we saved some to give you a feel for the public sentiment.

At this moment, my strongest feeling is not anger but shame. “Can you do that? Do you understand?” is asked [by the authorities] at each, one, of us.

“Can you do that?” “I can”

“Do you understand?” “I do”

What causes one to cry in anguish is that this age [of our’s], under this sun, is [enveloped] by darkness.”

#Can you do that? Do you undersrtand?#

They have [fighter] planes, they have tanks, they have no [moral] bottomline.

Perhaps at the beginning, bats were truly the culpruit (bringing disease)

But you and I now know

The murder does not [come] on black wings

[China’s core socialist values:] prosperity, democracy, civility and harmony, freedom, equality, justice, rule of law, patriotism, dedication, integrity, friendship.

Can you do that? Do you understand?

At its core, millions and millions of Chinese people relate to Dr Li. They see him as someone that was doing the right thing amid a crisis, and the authorities gagged him and forced him into submission.

Dr Li was humiliated by the authorities. Millions of Chinese people routinely suffer such indignity.

In Dr Li, they see themselves. They see oppression. They see incompetent local authorities. And a disregard for the rule of law.

Many are just sick of the bullshit and oppression in this difficult time. The current crisis amplifies all the grievances they have with the party-state, and highlight key weaknesses, such as the lack of transparency and accountability in China’s political system.

The Chinese Government is now in damage control, with the National Supervisory Commission sending out a team to Wuhan to thoroughly investigate the issues related to him — likely looking for a scapegoat.

While we are not at the point of street protests, and there is little likelihood that this crisis will bring down the current regime, what we need to remember that the system itself is crisis-prone because of structural issues. The China model, as it currently stands, is fundamentally broken.

Censorship and propaganda

After a two-week period of relative freedom in reporting of the novel coronavirus (or NCP, see below), we’re seeing a return of strict censorship and crackdown on “rumour spreading”.

Here is a recap of censorship and propaganda efforts related to the epidemic.

“Rumours” of a contagious infection has been sent around in December, mostly on WeChat among group chats.

On 1 January, Wuhan police announced that it had punished eight individuals (at the time, it was not publicised that they were in fact doctors) for spreading misinformation online. It later emerged that these doctors were warning others in WeChat groups about a new infection so that they can take extra precautions.

Apart from some very flat information releases with no accompanying public health warnings, it was all quiet from state media on this outbreak for a few weeks. During this time, it was business as usual, with people travelling on public transport for the Spring Festival and Wuhan city government even organising a banquet for 40,000 families.

This finally ended on January 20 with a directive from Xi Jinping to curb the spread of this virus:

The Party committees and governments at all levels must put people’s safety and health as the top priority and take effective measures to curb the spread of the virus, he said.

Xi ordered all-out efforts to treat patients, identify the causes of the virus infection and spread at an earlier date, strengthen monitoring and standardize treatment procedures.

Xi spoke of the need for the timely release of information and the deepening of international cooperation.

This is when state media started the flood of reports on the outbreak. Propaganda efforts started at the same time focusing on the heroic efforts by doctors (including wheeling out the SARS authority figure Zhong Nanshan 钟南山) , and construction workers who built the hospital in ten days.

Other news outlets such as Caixin was given some leeway in reporting, including the experiences of patients or those people who are inconvenienced by lockdowns. These experiences are not included as part of the state media propaganda push.

On 3 February, the Politburo Standing Committee met to discuss the coronavirus. The meeting emphasised that:

要做好宣传教育和舆论引导工作,统筹网上网下、国内国际、大事小事,更好强信心、暖人心、聚民心。要深入宣传党中央重大决策部署,充分报道各地区各部门联防联控的措施成效,生动讲述防疫抗疫一线的感人事迹,讲好中国抗击疫情故事,展现中国人民团结一心、同舟共济的精神风貌,凝聚众志成城抗疫情的强大力量。

Need to do a good propaganda job. Make plans for online and offline, domestic and international, major and minor matters, to strengthen confidence, warm people’s hearts and unify people. Need to thoroughly publicise CCP’s major decisions, fully report on the effectiveness of prevention and control measures of various regions and various departments. Vividly tell the touching stories of frontline personnel. Tell the China’s countering epidemic story well. Show the Chinese people’s unity and solidarity to fight the epidemic.

Since then, there has been a crackdown on “unofficial” reports of the epidemic, ostensibly to prevent the spread of misinformation, which was also the reason for the punishment of the eight doctors last month. Independent reporting and self-media are now severely restricted. Former human rights lawyer and famous citizen journalist, Chen Qiushi 陈秋实 , who went to Wuhan to report on the outbreak and who claimed in a video that he was not afraid of the CCP, is now missing and reportedly forcibly quarantined.

This shows that the party’s need to control the narrative is now much stronger. This renewed censorship effort is likely to affect information sharing, even among private citizens. WeChat accounts are being closed for forwarding unofficial reports of the epidemic. This will make people more reluctant to share any information they know.

*Yesterday, the State Council has decided to temporarily name the virus “Novel coronavirus pneumonia” 新型冠状病毒肺炎, simplified to “NCP” in English.

Chinoiserie

The following needs no introduction to China Watchers, but may be useful for those considering digging deeper into China:

China Heritage contains a repository of writings on China by world-renowned Sinologist Geremie Barmé and others. Rich, inspiring, and deeply-informed by historical and cultural understanding, this growing collection of articles is a seductive intellectual maze.

China Media Project does amazing work on analysing Chinese media and party media/rhetoric. A useful resource for understanding Chinese discursive environment, run by David Bandurski 班志远 and Qian Gang 钱钢 out of the University of Hong Kong.