Brief #45: national consciousness, domestic violence, public opinion on China

China Neican is a weekly column on the China Story blog edited by Yun Jiang and Adam Ni from the China Policy Centre in Canberra. Neican 内参 or “internal reference” are limited circulation reports only for the eyes of high-ranking officials in China, dealing with topics deemed too sensitive for public consumption. But rest assured, everyone is welcome to read what we write. You can find past issues of Neican here.

This week we look at Chinese national consciousness and Beijing’s identity project; the tragic death of a young Tibetan woman and the prevalence of domestic abuse in China; and the rising unfavourable views of China among developed countries.

1. Chinese national consciousness

A fortnight ago in Neican, we argued that Beijing’s assimilationist policies in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia are driven by its agenda to “forge a common [Chinese] identity” and as a result, “minorities are being forced to melt in a Han-dominant mainstream culture through state policies” This week, let's look at the ideological, intellectual and historical foundations of this project.

The CCP talks about its identity project in terms of building a “national consciousness”. With its diverse cultures and traditions, ethnicities, faiths/creeds, and collective memories, forging a common national identity/consciousness among the peoples of the People’s Republic is an imposing task.

Qing and Republican eras

First, some context...the Great Qing was a multi-ethnic empire ruled over by a Manchu dynasty allied with the Han elite. Nationalism (in the Western sense) was foreign to most denizens of the Qing Empire. People then had multiple identities and affiliations depending on their clan/family, locality/region, ethnicity, faith/creed and profession, instead of an overriding one based on the nation-state.

Chinese national consciousness started to develop in the late-19th and early-20th century in response to Western encroachment. For reformist thinkers and revolutionaries alike, a common national consciousness was deemed necessary for China’s very survival. For example, the first principle of Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People (三民主義) is the Principle of Minzu (民族主義), that is, nationalism. In fact, civic nationalism (as opposed to ethnic nationalism) was deemed to be so important that the first flag of the Republic of China was designed to symbolise the coming together of five major peoples (Han, Mongols, Tibetans, Manchus, and the Muslims) under one new nation. The irony was, of course, that the republican revolutionaries were staunchly anti-Manchu.

First national flag of Republic of China used between 1912 and 1928. Reminds us of the LGBTQ rainbow flag a little!

Chinese national consciousness was given a massive boost in the 1930s and 1940s during the war against Japan. As Rana Mitter’s Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945, vividly illustrates, the colossal efforts involved in mobilising the entire Chinese populace for war led to the coalescence of Chinese national consciousness where little of it was evident before the war.

CCP’s identity project

Under Xi, the political lingo for its identity project is the “Consciousness of Chinese National Community” 中华民族共同体意识. This project has similarities to national identity projects of Western countries in the 19th and 20th centuries in so far as they are exclusionary, coercive, state-driven, and assimilationist. Despite the lack of overt racism in Beijing’s idea of national consciousness, discrimination against ethnic minorities is inherent in its assimilationist underpinning, which amounts, in the eyes of some, to cultural genocide.

“Consciousness of Chinese National Community” is an idea that has been under development for some years. This formulation was first raised by Xi during the Second CCP Central Symposium on Xinjiang-related Work 第二次中央新疆工作座谈会 in May 2014 in the context of Beijing’s Xinjiang strategy.

The scope of this formulation expands to include work related to all ethnic minorities later that year at the CCP Central Work Conference on Ethnic Minorities 中央民族工作会议.

The concept was elevated in importance again three years later in October 2017 at the 19th Party Congress when it made it into Xi’s work report to party delegates. This time it was framed as part of the CCP’s United Front strategy:

统一战线是党的事业取得胜利的重要法宝,必须长期坚持...找到最大公约数...全面贯彻党的民族政策,深化民族团结进步教育,铸牢中华民族共同体意识,加强各民族交往交流交融,促进各民族像石榴籽一样紧紧抱在一起...全面贯彻党的宗教工作基本方针,坚持我国宗教的中国化方向,积极引导宗教与社会主义社会相适应。

The United Front [strategy and system] is the key to victory for the Party's cause, and must be maintained over the long term... [we must] find the greatest common ground...comprehensively implement the Party's ethnic policy, deepen education on national unity and progress, forge a firm sense of the Chinese national community, strengthen exchanges and intermingling among all ethnic groups, and promote all ethnic groups to cling to each other like pomegranate seeds...Comprehensively implement the Party's basic policy on religious work, persist in the sinicization of China's religions, and actively guide religions to adapt to socialist society.

(emphasis added)

The concept was further clarified and expanded upon in October 2019 when Beijing issued a document titled Opinions on comprehensively progressing ethnic unity work and forge and consolidate the Chinese national community 《关于全面深入持久开展民族团结进步创建工作铸牢中华民族共同体意识的意见》. The document explains why national identity is crucial in the following way:

中华民族共同体意识是国家统一之基、民族团结之本、精神力量之魂...铸牢中华民族共同体意识...是推进民族团结进步事业发展的必然要求,也是实现中华民族伟大复兴中国梦的必然要求。

The consciousness of the Chinese national community is the foundation of national unity, the foundation of national solidarity and the soul of spiritual strength...[We must] forge the consciousness of Chinese national community...[because] it is an inevitable requirement for advancing the cause of national unity and progress, as well as for realising the Chinese dream of the great national rejuvenation.

A “national consciousness” fashioned by the CCP is seen as critical to maintaining the Party’s rule. This idea influences Beijing’s policies with respect to ethnic minorities, religion, education, media, and internal security across the length and breadth of China. It has real ramifications for hundreds of millions of people in China, from Muslims in political re-education camps, to school students in Inner Mongolia, to protesters on the streets of Hong Kong.

2. Lamu and domestic violence

Lamu was a Tibetan social media celebrity on Douyin, which is TikTok in China. She was known for showcasing her life around her Tibetan village (in Sichuan), spreading smiles and positive energy despite her simple life. Last month, in the middle of her livestream, her ex-husband appeared, stabbed her, doused her in petrol, and set her on fire. She died two weeks later.

This incident again reignited uproar on domestic violence issues in China. According to reports, the perpetrator has continuously harassed, threatened and beaten Lamu in recent years. However, when these incidents were reported to the local police, it was met with a dismissive attitude.

According to official statistics, around a third of Chinese women have experienced physical domestic violence. On average, a Chinese woman experiences domestic violence 35 times before she calls the police. And no wonder, because 80 per cent of women calling the police for domestic violence are ignored. In Lamu’s case, despite the history of (public) domestic violence, Lamu’s ex-husband was given custody of their children. In another case last year, a court denied an application for divorce for a woman who was paralysed after jumping out of a window to escape domestic violence. As a result, around two-thirds of women who commit suicide in China do so due to domestic violence.

China passed the Anti-Domestic Violence Law only in 2016, finally criminalising domestic violence. However, the issue of domestic violence is not only a legal issue but also a social and enforcement issue. Domestic violence is still considered by many law enforcement officials as a “family matter” rather than a crime. As elsewhere, police is a male-dominant occupation in China. Without proper training and socialisation, the attitude of police usually mirrors the patriarchal attitude in society. Therefore, police can be more sympathetic to the perpetrator of domestic violence, with officers occasionally reprimanding the victim.

The conversation around domestic violence in China is still focused mostly on physical abuse. Attention probably won’t be given to other types of domestic violence recognised in countries such as Australia (e.g., psychological, emotional or financial abuse) before more is done to address physical abuse.

Unfortunately, in some respects, gender inequality has increased since the beginning of “reform and opening up”, for example, a widening pay gap. Yet grassroots feminist movements, like other social movements not sanctioned officially, are faced with crackdowns by authorities in China. This makes bottom-up change difficult. Meanwhile, top leadership in China are overwhelmingly male-dominated, making gender issues a low priority.

3. Unfavourable views of China

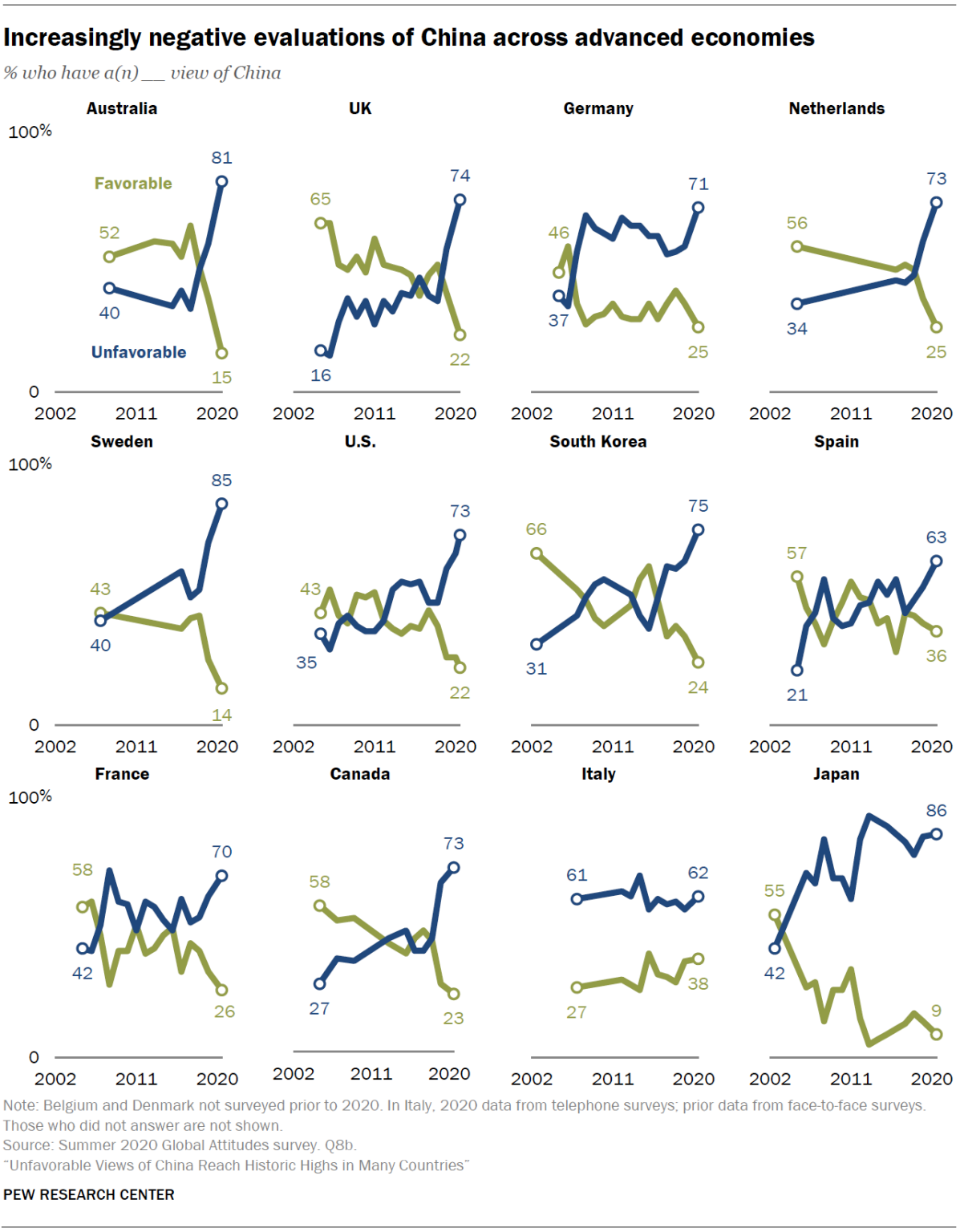

Recent Pew Research Centre data shows that public opinion of China has deteriorated in 14 developed economies, especially in this year. Out of these countries, negative views of China are the highest in Japan, Sweden, and Australia. The surveys were conducted in June and July with 14,276 respondents in total.

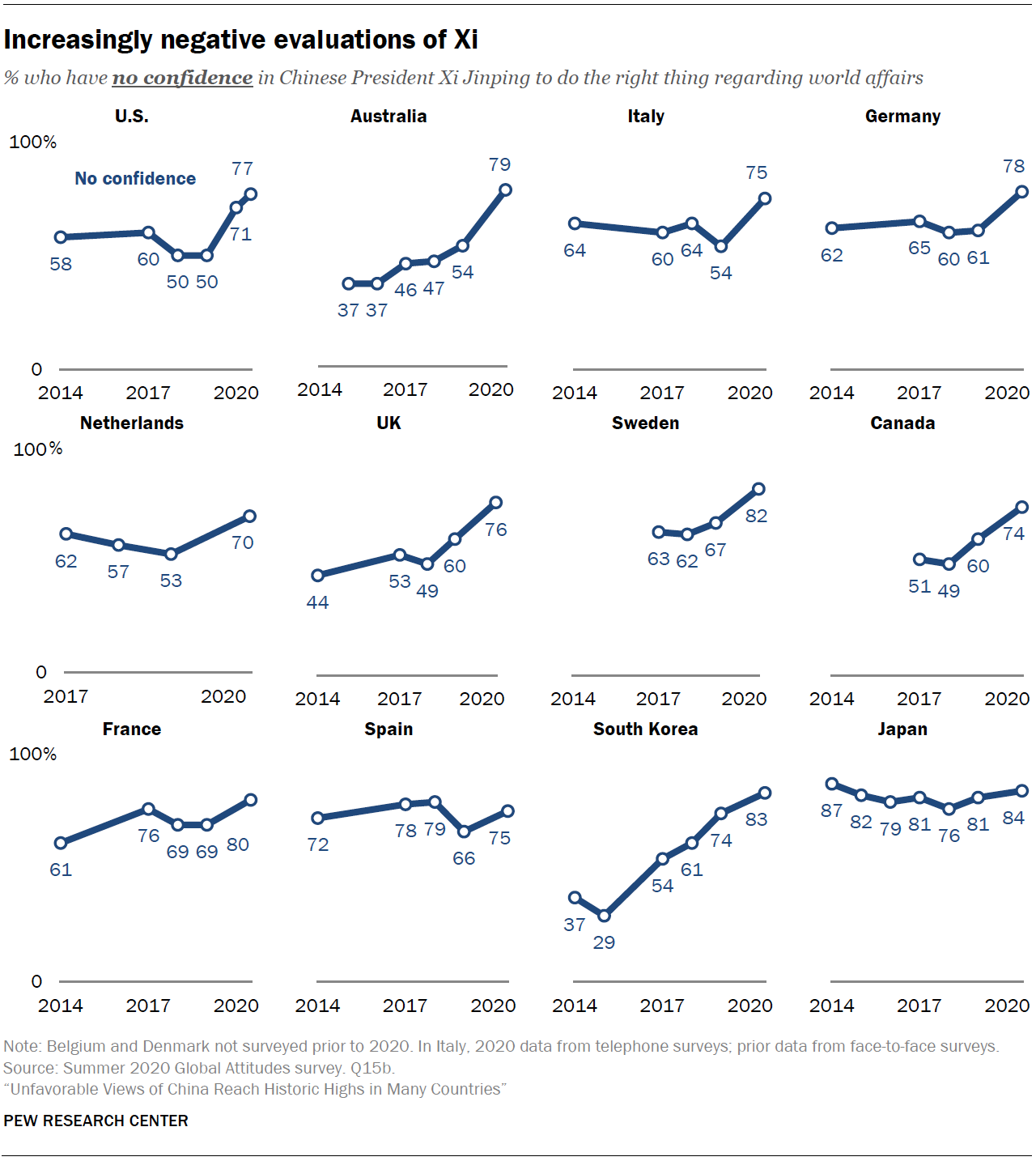

In those countries, confidence in Xi to do the right thing regarding world affairs has also decreased. The negative evaluations of Xi are the highest in Japan, South Korea, and Sweden. Other world leaders including, Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron and Boris Johnson, came out way ahead vis-a-vis Xi. However, confidence in Xi was still higher than in Trump.

Concerns about China are not only rising in countries with developed economies. In January, the State of Southeast Asia 2020 survey found that among countries in the region:

China is seen as the most influential economic and political-strategic power in the region, and outpaces the US by significant margins in both domains. However, China's growing influence is not well-received by the region. Among respondents who view China as the most influential economic power, 71.9% are worried about its expanding influence. This negative sentiment is echoed by respondents who consider China to be most influential in the political and strategic sphere, with 85.4% expressing their concern.

Data from recent surveys are not surprising, as China appears to have abandoned Deng’s low-profile approach of “hiding capacities and biding time”. Under Xi, China has become increasingly assertive internationally and more prone to the use of coercive instruments of statecraft to achieve its foreign policy objectives. As we wrote back in April:

China’s rising power and stature certainly has something to do with its new-found diplomatic assertiveness. But there are at least two other possible drivers. First, the rising pressure on the Chinese bureaucracy to respond forcefully to external criticism. Xi’s lofty promises of national rejuvenation require China to be respected on the international stage. Perceived disrespect, that in Beijing’s perception based on “incorrect” views, biases, and malign intent, requires an aggressive rejoinder.

The second is the increasing nationalistic tone of public discourse in China. The empirical evidence for the linkage between China’s rising popular nationalism and its foreign policy is unclear. But popular nationalism constrains Beijing’s spectrum of foreign policy options since perceived weakness and inability to defend China’s interests and dignity has costly public opinion ramifications.

While internal drivers are giving rise to “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy which plays well with the domestic audience, the aggressive tone of Chinese diplomats is damaging China’s standing abroad.

Love and fear

All else being equal, China would prefer people in other countries to have a more positive perception of it. However, international public opinion is only one consideration among many in Beijing’s calculus. Sometimes other strategic objectives override the need to be seen as affable. And to further illustrate that international image and power do not necessarily go hand-in-hand: while global perception of the US has fluctuated, its power still stands.

Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince muses on the interplay between love and fear in the exercise of political power:

It is much safer to be feared than loved because...love is preserved by the link of obligation which, owing to the baseness of men, is broken at every opportunity for their advantage; but fear preserves you by a dread of punishment which never fails.

To achieve its strategic objectives, China needs to balance love with fear. Right now, among the international community, there is neither enough “love” for, nor enough “fear” of, Beijing. Until its coercive power becomes more advanced, it would be wise for Beijing to try and patch its international image.

This week on China Story:

- Michiko Weinmann, Rod Neilsen and Sophia Slavich, Politicisation of teaching Chinese language in Australian classrooms today: The politicisation of Chinese language study in Australia promotes the idea that learning Chinese is useful to Australians for purely practical economic reasons, such as being able to conduct business or trade. This has particular implications for Languages teaching and learning, as it reduces multilingualism and its associated benefits—intercultural competence, literacy, language awareness and critical thinking—to a strategic resource.