Brief #85: gender diversity, enforced morality, gig workers

1. Queer China

The Chinese leadership is deeply conservative on certain social issues. When it comes to gender norms or “family values”, their stance resembles the Christian right in the West.

In the past year, the government has tried to constrain gender expressions and eliminate gender diversity. I have noted previously the renewed push for “traditional family values” and “traditional feminine virtues”, in the context of China’s fertility policy. Furthermore, the Ministry of Education early this year highlighted the “feminisation” of young men as a problem that needs to be solved by cultivating “masculine energy”. These measures aim to pigeonhole individuals into two predetermined gender expressions (that are aligned with their perceived biological sex).

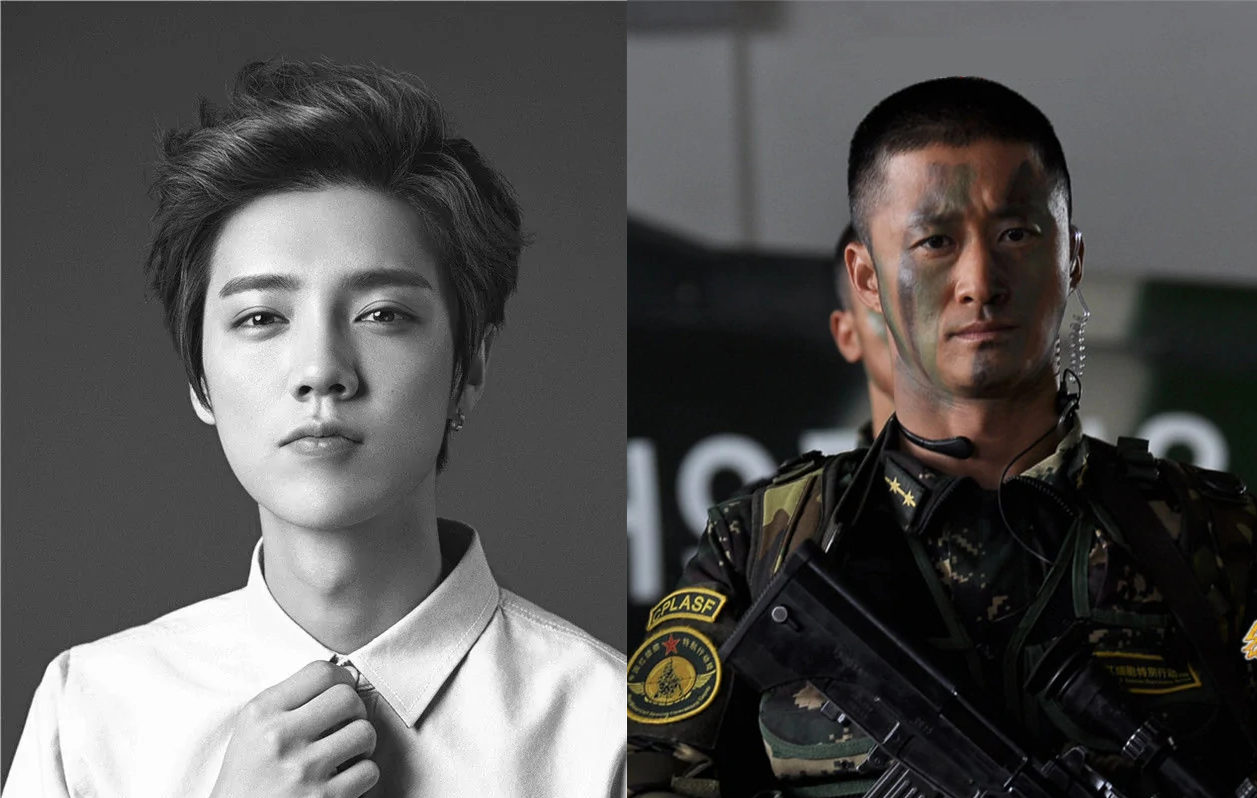

This week, the National Radio and Television Administration published a notice that, among other things, banned “effeminate men” 娘炮 from screens and calling it a “perverse aesthetic” 畸形审美. This is part of a project to instil the “correct aesthetic” that includes acting styles, costumes, and makeup.

According to the notice, the aim is to maintain “cultural confidence” and promote “traditional culture”, “revolutionary culture” and “socialist culture”. Of course, this ignores the fact that in China (as is in most cultures), diversity in gender expressions, just like homosexuality, is often part of the “traditional culture”.

While the Chinese Government is insisting on strict gender norms, the Taiwan Government has taken a different approach. Its Ministry of Culture produced this meme in response to China’s notice:

This message was also promoted by Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare. And this is a message that I wholeheartedly endorse and support.

Enforcing strict gender norms does enormous harm to LGBT+ people in society, including nonbinary and genderqueer people. But even for young people that are cishet (cisgender and heterosexual), it can foster unhealthy behavioural expectations such as “boys don’t cry”.

This year, there have been some concerning crackdowns on LGBT+ groups. In February, a Chinese court ruled in favour of a publisher that described homosexuality as a mental disorder in a university textbook. The court said the description was not an intellectual error, even though homosexuality has been removed from the list of mental disorders in 2001. In July, WeChat shut down some university student-run accounts. In August, Shanghai University asked for a list of LGBT+ students.

As China becomes more authoritarian, it is attempting to enforce a degree of conformity on individuals by eliminating diversity in culture (Uyghurs), sexuality and gender expressions. This is a tactic also used by right-wing governments around the world. In Russia and Hungary, the rights of LGBT+ people are also on the retreat.

2. Political correctness

While the ban on “effeminate men” has attracted attention, the National Radio and Television Administration notice is far more wide-ranging. The published notice works in tandem with last week’s order from the Cyberspace Affair Commission to tighten regulations on China’s celebrity fan culture.

The notice included measures to “resolutely boycott immoral actors”, who have “incorrect political stances”. It also includes measures to “boycott high pay for shows/films”.

It will become even more difficult for TV/film producers and public figures to avoid politics. Actors and celebrities are not only expected to toe the party line as before, but now the pressure is on for them to actively promote it at every opportunity. Anyone who dares to deviate from the “correct political stance” would suffer severe consequences and be boycotted by government order. When it comes to power between the state and celebrities in China, the state has the absolute upper hand.

Producers must also be more cautious about what sort of films or TV shows they produce and invest in. We should expect more films and TV shows with nationalistic elements, that praises the CCP and promote “positive energy”. More “realism” and military; less fantasy and social critique. So I guess 皓衣行 (Immortality), the upcoming Boy Love Xianxia drama, will never make it.

Celebrities will also need to be on their best behaviour in order to conform to the “moral standards” set by the government. In practice, this means more charity work and less self-indulgence. They must strive to be an upstanding citizen and good role model first and foremost.

The government has taken a paternalistic approach on a number of social issues, from gaming to the entertainment industry. While many people in China believe that the government is acting to curb “vices”, such as gaming addictions and celebrity idol-worshipping, it’s unclear whether they would agree that the government should play an active role.

But where does it stop? While most people may have applauded the crackdown on party and state officials committing vices, it’s another matter for them to enforce their “morality” on everyone in the country. Again, legislating “morality” is the sort of thing that right-wing governments have done around the world.

Ultimately, such paternalism shows that the CCP does not trust the Chinese people to make their own decisions without the party’s guidance.

3. Gig workers

Didi, which is currently being investigated for data protection violations, is helping its drivers form a union. It’s important to remember workplace unions are not independent but operate under the All-China Federation of Trade Unions, a party-controlled body.

Earlier this year, delivery drivers (who like Didi drivers are also gig workers) for companies such as Meituan and Ele.me tried to organise, but their lead organiser was detained by the local police.

There is a familiar pattern in China on labour issues. While the government is criticising companies for their labour practices, it is also trying to stifle grassroots labour movements. Labour movements must be organised under the control and guidance of the government, and never go against party priority.

As Didi is setting up a union, a Hong Kong University PhD student researching labour movements in China was detained in Nanning for “subverting state power”.

The government is worried about anything that can potentially organise and challenge state power, from religions/cults to celebrities, and to labour organisers. To deal with these forces, it uses both co-option and crackdown. In the case of the labour movement, it is cracking down on leaders and co-opting the masses through unions.

While unions have been criticised for their lack of independence, sometimes workers can still use them to pressure management. In any case, the fact that Didi is helping workers to form a union shows that labour issues among gig workers have gained prominence. I just hope that it is more than a superficial change.

Neican Brief is made possible by the support of the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University.