Brief #82: celebrity & nationalism, disaggregating "Chinese influence", dissenting intellectuals, sexual assault

1. Celebrity and Nationalism

Every now and then I turn my attention to celebrity news/gossip — sometimes they can be illuminating about popular trends, government attention, and the interaction between the two.

After the Kris Wu sexual assault allegations, the next celebrity to experience huge controversy is Zhang Zhehan 张哲瀚. Zhang became popular after starring in the recent Boy Love-adapted drama Word of Honor (山河令, available on YouTube and Netflix). Just before this controversy, his star power was ascending, reaching near the top of mainland male star ranking.

However, that quickly changed with allegations that he has a close affinity with Japan. The controversy started with photos of him attending a friend’s wedding at a Japanese shrine last year and him visiting the controversial Yasukuni Shrine. His frequent visits to Japan was also seen as evidence online that he is “close to Japan”, or more extremely, that he’s a Japanese spy.

All of these happened right around the anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II (15 August) and the Japanese Defence Minister’s visit to the Yasukuni Shrine — so anti-Japanese and nationalistic sentiments are particularly high in China. At the same time, the Chinese Government is also actively discouraging celebrity worship. This is the perfect timing to make an example out of someone.

As a result of this controversy, many sponsors have ended contracts with him, and there are fears that dramas starring him currently in post-production may never be released. After all, the demographics of fans overlap with the demographic of “Little Pink” — young women. Zhang’s apologies did not seem to quell public anger so far.

In the eyes of Chinese nationalists online, visiting the Yasukuni Shrine is worthy of condemnation and boycotts, due to its high symbolic value. And once a celebrity has lost their halo, even seemingly innocuous actions, such as visiting Japan frequently, is interpreted as further evidence of villainy.

This episode is also notable for the fact that People’s Daily, the official mouthpiece of the CCP, has weighed in. Its Weibo account criticised the actor. This can be seen as an “official verdict” and a signal for attacks and boycotts to continue.

In most nationalism examples, it is difficult to separate out the role played by the state in instigating or inflaming nationalism and the role played by the masses. They often reinforce each other, but other times, they can work against each other. In this case, the state played a role in drumming up nationalism around the anniversary as well as issuing a statement on the incident.

Nationalistic criticisms and boycotts targeting celebrities is hardly unique to China. In the early 2000s, the Dixie Chicks were criticised and blacklisted for their anti-war stance. After 9/11, many actors also made videos describing how much they love American flags — videos that would fit right in with nationalist propaganda in China. But such nationalism seems cringe-worthy now, so it appears that nationalism has better staying power in China, possibly due to stronger official support.

2. Disaggregating “Chinese influence”

Andrew Chubb wrote an insightful paper PRC Overseas Political Activities: Risk, Reaction and the Case of Australia. He argues that:

Responding effectively to the challenges presented by the PRC’s overseas political activities starts with disaggregating the distinct risks they pose.

In the conclusion, he drew an interesting parallel:

Titled Silent Contest (较量无声), the film depicted a vast conspiracy among Western governments, civil society and citizens coordinating consciously or unconsciously (the distinction was irrelevant) to infiltrate and subvert China’s rise under the CCP. A similar mode of thinking has, ironically, also gained ground within policy discussions on the PRC’s overseas political activities in liberal democracies. The parallels between Silent Contest and the influential Australian polemic Silent Invasion run deep, and are far from a lone example.

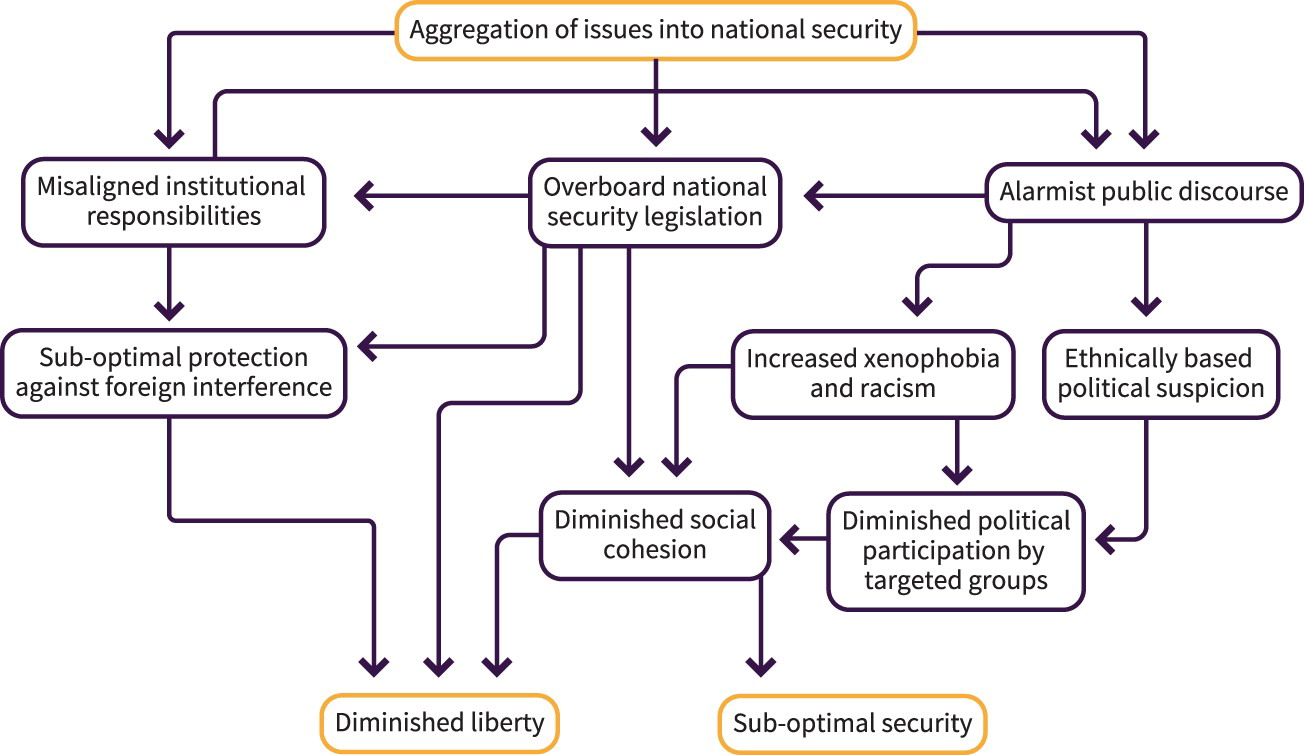

Chubb disaggregated risks posed by the PRC’s overseas political activities into three categories: national security, civil liberties, and academic freedom. The national security risks include electoral interference and elite co-optation. Other risks such as extra-territorial suppression of dissent, Chinese language media platforms, and co-optation of community organisations came under the civil liberties risks category.

Treating all risks posed by PRC as one overarching national security risk, as Australia has done, has not only diminished civil liberties in Australia but also left some of the most impactful PRC activities unaddressed. This is what I found the most interesting from Chubb’s paper.

For example, the Espionage and Foreign Interference Act only criminalised foreign interference against Australian citizens, “leaving a significant loophole for authoritarian regimes and their supporters to continue coercing overseas students and recent migrants”.

At the same time, the Act introduced a crime of ‘dealing with’ classified information, including hearing classified information, and it does not require such information to be shared with any foreign country.

These are just two of the many criticisms raised by law experts and human rights researchers on the legislation. To me, it seems that the foreign interference legislation is more concerned about protecting the state (and the government) rather than individuals. Indeed Chubb observes that “countering foreign interference against civil liberties is a relatively low priority compared with the national security aspects of foreign interference”.

The paper is comprehensive and details many other issues that readers of Neican would be familiar with, such as freedom of speech in universities, and rising racism and suspicions. I highly recommend the readers to check out the paper in full — it’s very readable. If you have access issues, please DM the author.

3. Dissenting intellectuals

Despite increasing authoritarianism under Xi in China, there are still some courageous dissenting voices. One of them is Xu Zhangrun 許章潤. Xu has been persecuted for his views. Although he is not in jail, he has been fired from his job at Tsinghua, forced to live off his savings and is under surveillance. Yet he has continued to write, and Geremie Barmé has translated his works at China Heritage.

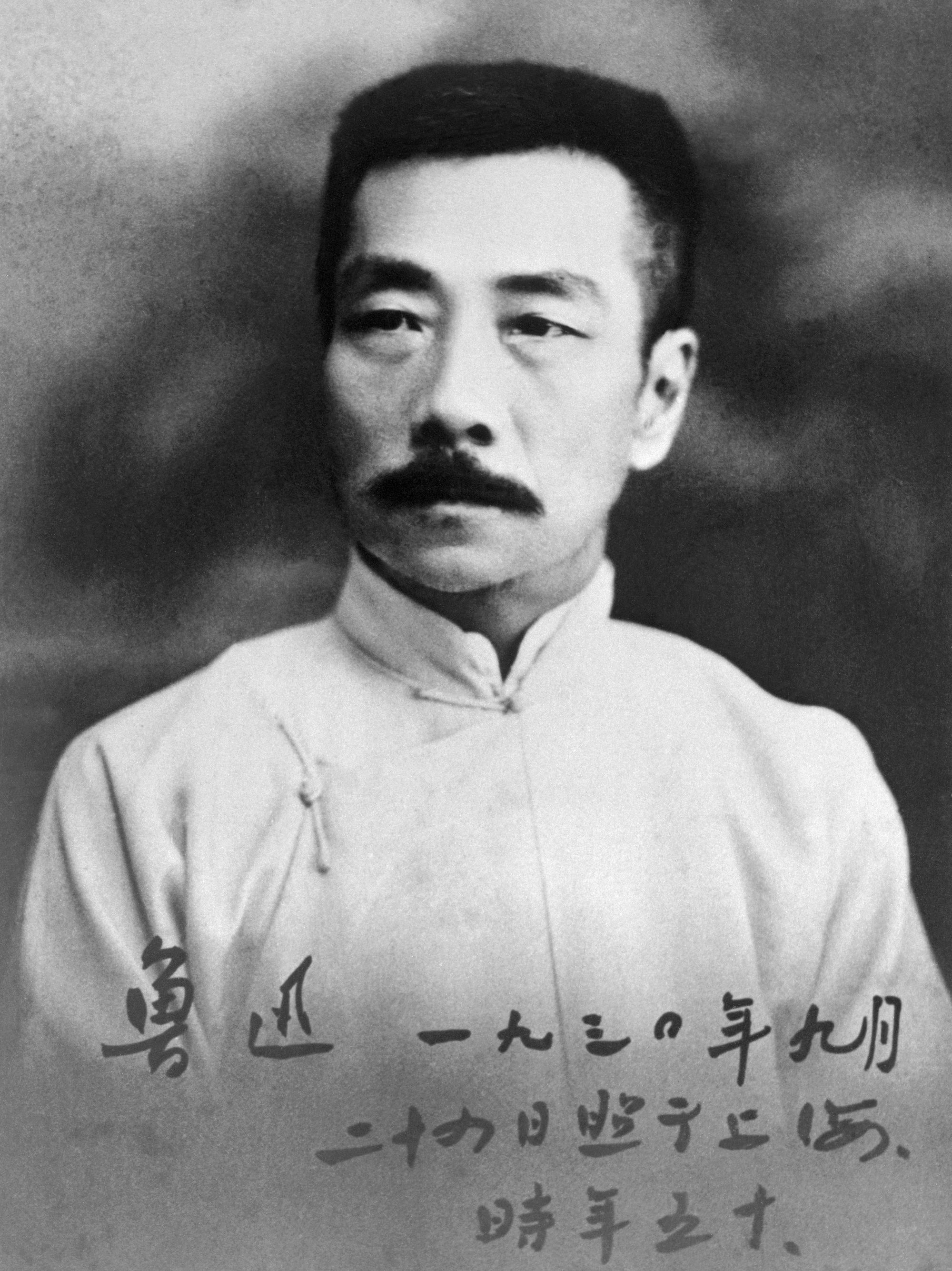

How the CCP treats Xu stands in contrast to how the CCP has lionised some early dissenting intellectuals. The most prominent example being Lu Xun 魯迅. When I lived in Shanghai, I lived near Lu Xun Park and my primary school had a portrait of Lu Xun.

Lu Xun was a dissenting intellectual — he was harshly critical of Chinese society at the time and also of the ruling Nationalist Government. So naturally, the CCP promoted him and his works after the PRC was established (he had died by then — dead people are always easier to appropriate). But would the CCP welcome a dissenting figure like Lu Xun? Of course not, many intellectuals were purged or killed, from the Yan’an Rectification Campaign in the 40s to the Cultural Revolution in the 70s.

Supporting dissent as a revolutionary party is different from supporting dissent as a ruling party. Many parties support intellectual freedom when they’re not in power, but their interests change as soon as they get in power. This happens even in democracies, but there are more constraints on cracking down on dissent in these countries.

The flip side of this are people who always support those in power. There are many who support increasing state power in order to counter external threats (such as those posed by the CCP). Sometimes they are willing to overlook effects on civil liberties. I often wonder what would happen if these anti-CCP crusaders grew up and lived in China instead. Would they give the same advice to the CCP?

4. Sexual assault — Alibaba and Kris Wu

A female Alibaba employee alleged that she was raped by her manager on a work trip. She reported the incident to the company but was mostly ignored until she posted on social media. After her post has gone viral, both the company and the local police finally took notice, with Alibaba pledging to do more to prevent sexual assault.

The technology industry is a male-dominated industry and has known problems with misogyny. Unfortunately for victims of sexual harassment and sexual assault, it often requires going public for the company to take action. It was the same with the Australian Parliament this year. Brittany Higgins also had to make public accusations. Before that, the parliamentarians were more interested in covering it up. Yet, by going public, the victims of sexual assault had to deal with intense publicity.

The Alibaba allegations came right after the Kris Wu allegation. Kris Wu was arrested in Beijing on suspicion of rape. Wu is a Canadian citizen, so this is a consular case for the Canadian embassy. However, unlike the cases of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, who was sentenced to 11 years, the case of Wu is unlikely related to the bilateral relationship between Canada and China.

The Chinese Government, pushed by feminist activists, appears to be taking sexual assault more seriously now. Although the government is trying to take credit for the small progress, it could not have happened without the work of feminists in China.

Neican Brief is made possible by the support of the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University.