Brief #59: Xi's vision, US Indo-Pacific strategy, sanctions

Subscribe now. You’ll be in the good company of thousands of policymakers, researchers and others. If you are already a fan, please spread the word:

1. Strategic vision and Xi’s timescape

Xi Jinping proclaimed that China has entered a “new development stage” (新发展阶段) in a speech to the Party’s top cadres on January 11. This speech deserves our attention because this is the first time a top Chinese leader has articulated this new concept.

So what is this “new development stage”?

Simply put, the Party marks 2021 as the start of a new stage for China’s socioeconomic development. This is because the first centenary (100 years since the CCP’s founding) is this year. For this occasion, the CCP will declare victory over its first centenary goal. And then it will shift its focus to the second centenary goal.

Before diving into the “new development stage” concept and Xi’s timescape, let's first recap the CCP’s broader strategic vision...

Strategic objectives

Beneath CCP regime survival, sits two overarching strategic objectives. According to Xi’s report at the 19th CCP National Congress in October 2017:

[T]he overarching goal of upholding and developing socialism with Chinese characteristics is to realize socialist modernization and national rejuvenation...

新时代中国特色社会主义思想,明确坚持和发展中国特色社会主义,总任务是实现社会主义现代化和中华民族伟大复兴...

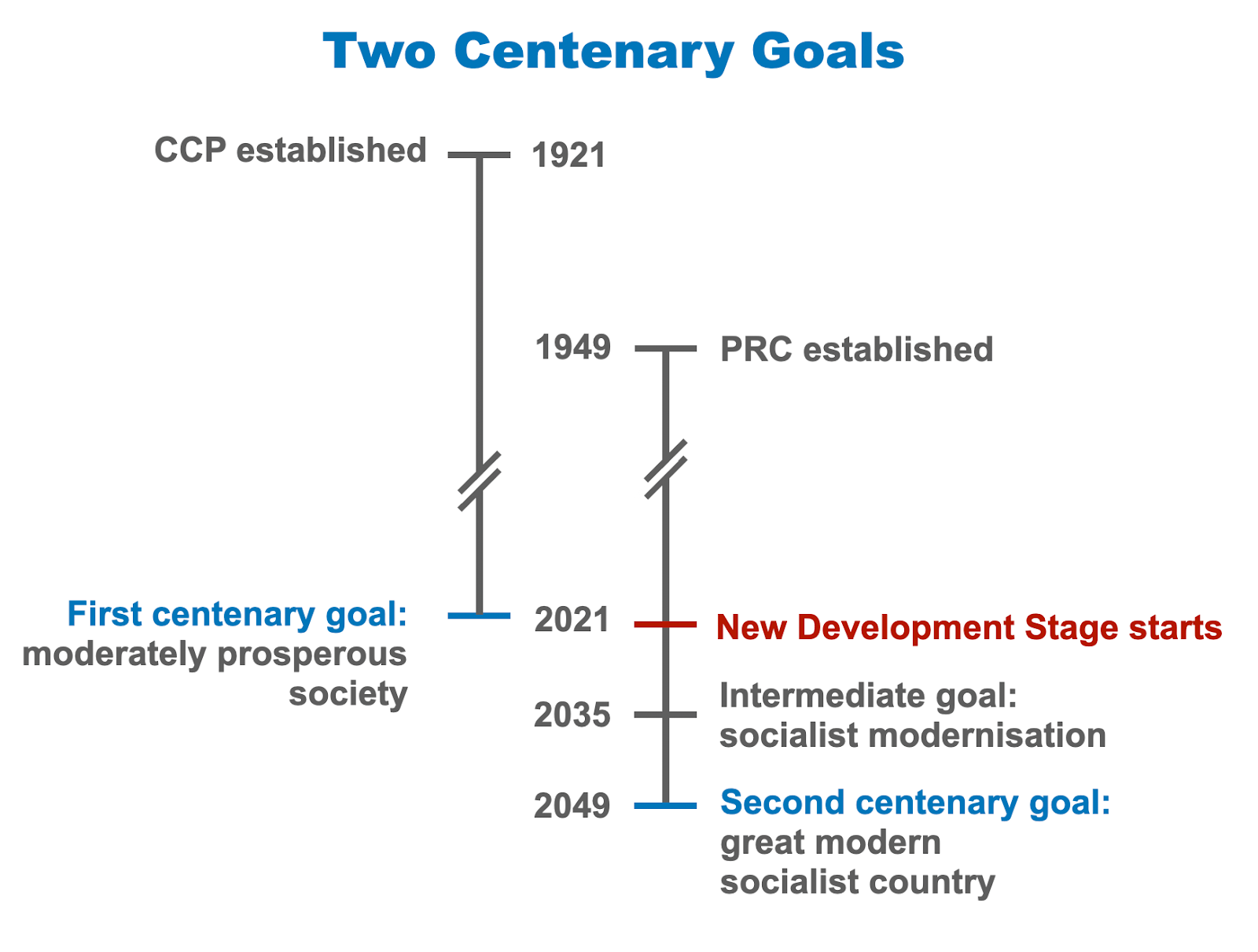

In order to achieve “socialist modernisation,” the Party has laid out two milestones known as the Two Centenary Goals (“两个一百年”奋斗目标). The first centenary started counting from the founding of the CCP in 1921. The second centenary started counting from the establishment of the PRC in 1949.

By the end of the first centenary, the Party’s goal is for China to finishing building a “moderately prosperous society in all respects” (全面建成小康社会). Poverty alleviation is the most significant criteria here. By the end of the second centenary, the Party’s goal is to build China into a “great modern socialist country” (社会主义现代化强国).

Graphics courtesy of Katharina Ni

According to the CCP’s plan, once China completes the building of a “moderately prosperous society in all respects” in 2021, it would then redirect its focus to a two-phase process to reach the second centenary goal. The first phase runs between 2021 and 2035. By the end of this first stage, China would have basically realised socialist modernisation (基本实现社会主义现代化), and in doing so:

- significantly increased its economic and technological strength;

- became a global leader in innovation;

- basically modernised its system and capacity for governance;

- significantly enhanced the social etiquette and civility of its people;

- grown much stronger in cultural soft power;

- grown considerably the size of the middle-income group;

- significantly reduced disparities between urban and rural areas, and between regions; and

- fundamentally improved in the environment.

The second phase runs between 2035 and 2049. By the end of this phase, China would have become a “great modern socialist country”, and in doing so:

- reached new heights in every dimension of material, political, cultural and ethical, social, and ecological advancement;

- modernised its system and capacity for governance;

- became a global leader in total national strength and international influence;

- achieved common prosperity for everyone; and

- enabled the Chinese people to enjoy happier, safer, and healthier lives.

To put it another way, by 2050, China aims to become a superpower with 2035 serving as an intermediate milestone.

Now, let’s go back to the “new development phase” concept...

New development stage

As discussed above, the start of the “new development stage” marks the transition from the completion of the first centenary goal to the pursuit of the second centenary goal.

Xi points out that in the “new development stage”, China’s socioeconomic development must be pursued with three understandings. One, achieving “common prosperity” is an economic issue, but also a major political issue for the Party’s rule. Problems with regional, urban vs rural and income disparities need to be proactively tackled.

Two, there is a need to adopt more precision and pragmatism policies in tackling the problems of unbalanced and insufficient development, and actually achieve high-quality development.

Three, given major domestic and international changes, Party cadres must be extra vigilant in monitoring risks and resolving challenges.

Xi characterises the significance of the “new development stage” in the following way:

The new stage of development is a new stage in which our Party leads the people to usher in a historic leap from “standing up”, “getting rich” to “becoming strong”. Since the founding of New China, especially after more than 40 years of unremitting struggle since the reform and opening up, we already have a strong material foundation for starting a new journey and achieving new and greater goals. Soon after the founding of New China, our Party proposed the goal of building a socialist modern country, and the next 30 years will be a new stage of development for us to fulfil this historical ambition.

新发展阶段是我们党带领人民迎来从站起来、富起来到强起来历史性跨越的新阶段。经过新中国成立以来特别是改革开放40多年的不懈奋斗,我们已经拥有开启新征程、实现新的更高目标的雄厚物质基础。新中国成立不久,我们党就提出建设社会主义现代化国家的目标,未来30年将是我们完成这个历史宏愿的新发展阶段。

(emphasis added)

In the current official CCP orthodoxy, Party history (and by extension the history of the PRC) is boxed into three distinct time periods: “standing up,” (Mao era) “getting rich” (Deng era), and “becoming strong” (Xi era). This narrative tries to draw a straight line from Mao to Deng to Xi for current political expediency.

This is, of course, a selective telling of history. It sweeps under the carpet both the tragedies of the past and the unpredictability of the future.

2. US strategy for the Indo-Pacific

The Trump Administration, in the last few days remaining, has decided to declassify its Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific, formulated in 2018.

It's obvious from reading this document that the US Government has not followed its own strategy, especially with regards to alliances as well as economics and trade. So what is the point of this strategy document if it was not followed or implemented? This reminded us of the Australia in the Asian Century White Paper, released in October 2012 and forgotten less than a year later.

Declassification and publication

The document was previously classified SECRET and restricted for viewing/accessing by US nationals only. Usually, such documents would only be declassified and released 30 years later.

Parts of the document (national security challenges, interests of the US in the Indo-Pacific, desired end states, and the substantial lines of effort) were classified SECRET because its release was deemed to cause “serious damage” to the US national security.

What has changed in the US national security threat environment in the last few years to warrant this declassification?

If the motivation behind the release was indeed to “reassure allies”, it is a very odd move. Allies are more reassured by US actions than the public release of a strategy document that was never even implemented. Such a document would not be enough to repair the damage that the Trump Administration has done to US alliances over the last four years, from tariffs to demands that allies pay more for US troops.

In another unusual move, the document was handed over to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation as an “Exclusive” before the public release, and was analysed by Rory Medcalf from ANU’s National Security College. At least Australia still has some headspace to follow the US foreign policy, when the US media is still preoccupied with the crisis facing US democracy following the storming of the Capitol by Trump supporters.

Some say that the document’s release may be intended to ensure continuity in the US foreign policy. Apart from the fact that the strategy was hardly implemented (and hence there is no continuity to speak of), previous transitions of government have never required a public release of a formerly classified document to ensure continuity.

Some claim that the release was to counter the argument that “Trump presidency has been a strategy-free zone”, then this document only shows that Trump presidency could not even follow its own strategy when it had one.

Assessment of the Strategy

The first thing that's obvious is that the US still aims to maintain its “strategic primacy in the Indo-Pacific”. Contrasting the prediction that the world will become more multipolar, the US Government was trying to prevent that from happening and work to maintain US hegemony. We don’t think such an aim is realistic, but “primacy” can be a flexible term when necessary.

Second, unsurprisingly, China features heavily in the strategy as an adversary. The first national security challenge is explicit about preventing China from establishing its spheres of influence. Six out of 14 assumptions are directly about China. Much of the lines of effort appears to revolve around countering China’s influence. Cooperation and partnerships with other countries in the region appear to be centred on this. India is frequently mentioned in relation to its value in countering China.

Third, economic issues such as trade and technology are prominent. It is notable that the first line of effort listed under “China” was on China’s industrial and trade policies. However, the strategy did not predict that the US would be perceived as a pariah on some trade issues. The strategy used the language of promoting “a liberal economic order” and “advance US global economic leadership”. Under Southeast Asia, the strategy called for the pursuit of trade agreements that “reduce the region’s economic reliance on China”. Quite clearly in this regard, the US Government has not followed its own strategy in the past three years.

Fourth, the strategy has a heavy focus on alliances. This was of course celebrated by many commentators in Australia. Professor Medcalf called it “alliance-driven strategy”. But it’s clear from the record of the Trump presidency in the past four years that allies were readily sacrificed for Trump’s “America First”.

3. Sanctions and anti-sanctions

The US has enacted more sanctions on China. In the past week, the US has banned the imports of all cotton and tomatoes from Xinjiang, citing forced labour concerns. This is in addition to last year’s sanction on cotton produced by Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. This ban will significantly affect the global apparel industry.

We previously noted that the existing general modern slavery legislations have not managed to eliminate modern slavery. Sanctions targeted at specific regions or companies may be more effective as compliance enforcement is likely easier. However, specific sanctions also mean modern slavery from different regions are treated differently.

Also this week, the US blacklisted Xiaomi, branding it “Communist military company”. Unlike Huawei, which is involved in building 5G infrastructure, Xiaomi is a consumer electronics company. It produces products such as mobile phones, vacuum cleaners, and home air purifiers. It is perhaps most famous for copying competitor’s designs, including Apple and Dyson. In China, its Redmi line is known for those who cannot afford iPhones. There is currently no public information linking Xiaomi to the PLA, and no such information was released by the US Government.

In response to the various earlier US measures against Chinese companies, China’s Ministry of Commerce has released an anti-sanctions order, titled Rules on Counteracting Unjustified Extra-territorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures (阻断外国法律与措施不当域外适用办法). The order provides remedies to companies that suffer losses from compliance of foreign sanctions. This means that a company that complies with US sanctions on China may end up having to pay compensation to Chinese companies who suffer losses from this compliance. Although this order appears to target companies, it is intended to pressure the US Government.

Zichen Wang from Pekingnology noted that the new order is modelled after the EU’s blocking statute, which is used to counter US sanctions against Cuba and Iran. The EU “does not recognise the extraterritorial application of laws adopted by third countries and considers such effects to be contrary to international law.”

Zichen Wang further notes that:

The logic in EU and China is largely the same: U.S. laws should not apply here; if somebody complies with them - or court rulings based on those designated U.S. laws - to cause harm to our companies, our companies can sue in our courts; if our courts rule in favor our companies, that somebody would lose money to our companies as payback, and the whole thing is a deterrent to the extra-territorial application of U.S. laws.

Chinoiserie

- Yangyang Cheng, in her beautifully written article 'China-watching' is a lucrative business. But whose language do the experts speak? muses about language, power and identity in the “China watching” circle:

As China develops from an impoverished backwater into the world’s second largest economy, many in the west have looked to it as fertile ground for promising careers. Their passion is not in Chinese history or culture, at least not as a priority. To the corporate elite, China is a market to be mined. To the security expert, China is a threat to be addressed. To the politicians and pundits, China is a “problem” to be solved. The lives and wellbeing of Chinese people, affected by policies, rhetoric and business deals, barely register in these discussions. Knowledge of the local language becomes irrelevant when the natives are presumed silent.

- One Uyghur person’s account of her experience in the camp in Xinjiang. Heartbreaking first-hand accounts such as this are very valuable due to the severe restrictions on reporting in Xinjiang.

- Decoupling - Severed Ties and Patchwork Globalisation, a report by European Chamber of Commerce in China and MERICS, found that: “while the trade war has largely failed in its goal of forcing firms back to their home countries, the technology war is inflicting real damage on companies and economies alike”.

- A profile of Rong Yiren, the Red Capitalist, by Neil Thomas, offers some lessons for Jack Ma.

- MAGA-land’s Favorite Newspaper: How The Epoch Times became a pro-Trump propaganda machine in an age of plague and insurrection: “For years, its anti-communism had seemed oddly beside the point. Then a deadly pandemic emerged in China, where the government muzzled whistleblowers and covered up the virus’s early spread. Suddenly, The Epoch Times’ wall-to-wall coverage of the “CCP virus” was being amplified across the American right. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who recently sat for an interview with the paper, pushed the hatched-in-a-lab theory”.

China Story

- William Yuen Yee, The RCEP is a Win for China: The signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership represents a setback for U.S. trade leadership and a significant win for China. While the historic free trade agreement that will add US$500 billion to world trade by 2030 is often inaccurately deemed “China-led,” it nonetheless strengthens China’s position in the Asia-Pacific. China will use the RCEP to help offset the effects of the U.S.-China trade war, increase the exchange of high-tech equipment to pursue the objectives of Made in China 2025 and its 14th Five-Year Plan, and ultimately augment its geopolitical influence.

- David C. Logan, China’s Missile Forces: Risks of Nuclear-Conventional Entanglement: The potential risks of nuclear-conventional entanglement in China’s missile forces has drawn increasing concern from American observers. This entanglement could increase the likelihood of nuclear use in a crisis or conflict. But much of the details of how and why that entanglement exists has remained unknown to analysts. In research recently published in the Journal of Strategic Studies, I find that while the risks of entanglement are less acute than other analysts have feared, they are real and likely to evolve. Significantly, American and Chinese strategists appear to have starkly different views of the dimensions, drivers, and risks of this entanglement. Addressing the risks will require concerted effort to reduce entanglement within China’s missile forces and to reduce the chances of misperception between China and the United States.

The China Neican newsletter is also published as a weekly column on the China Story blog. The name Neican 内参 (“internal reference”) comes from limited circulation reports only for the eyes of high-ranking officials in China, dealing with topics deemed too sensitive for public consumption. You can find past issues here.