Brief #119: Party Numbers 2021

The Central Organization Department published its annual Statistics Bulletin of the Communist Party of China (中国共产党党内统计公报) on June 29. The bulletin contains stats on Party membership, organisations and structure (as of the end of 2021).

Part 1 of this brief is a note by Yang Liu of the Beijing Channel newsletter. It summarises this year's stats and puts them into useful infographics.

Part 2 are thoughts by yours truly (Adam).

PART 1: The Communist Party of China, in numbers (by Yang Liu, with graphics by Lu Jia’nan, Beijing Channel)

Since 2013, unveiling the party's stats just before July 1 has become somewhat of an annual tradition for the CPC Organization Department. This year’s numbers were unveiled on June 29 and reflected the party’s members and structure status as of the end of 2021.

(2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021)

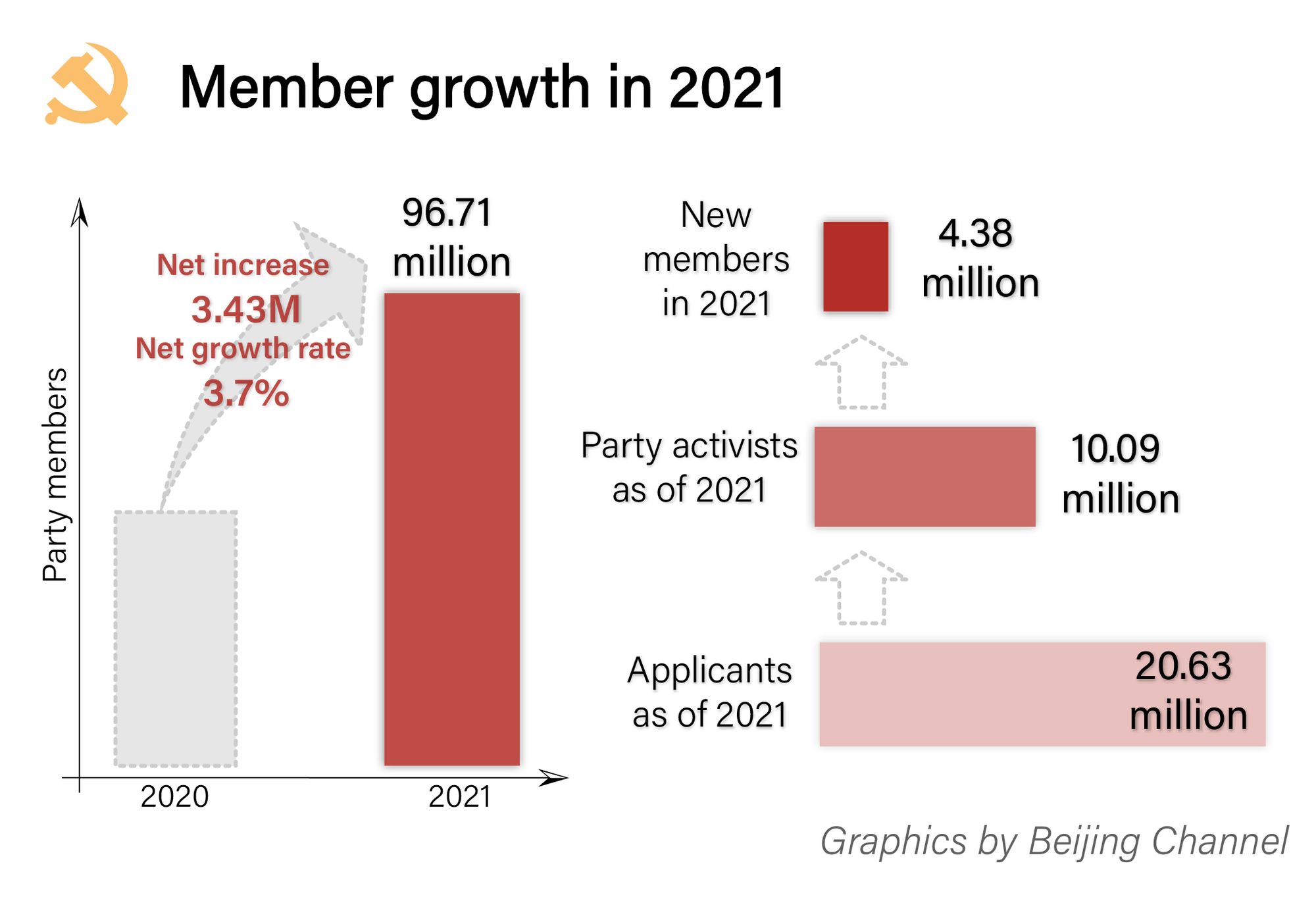

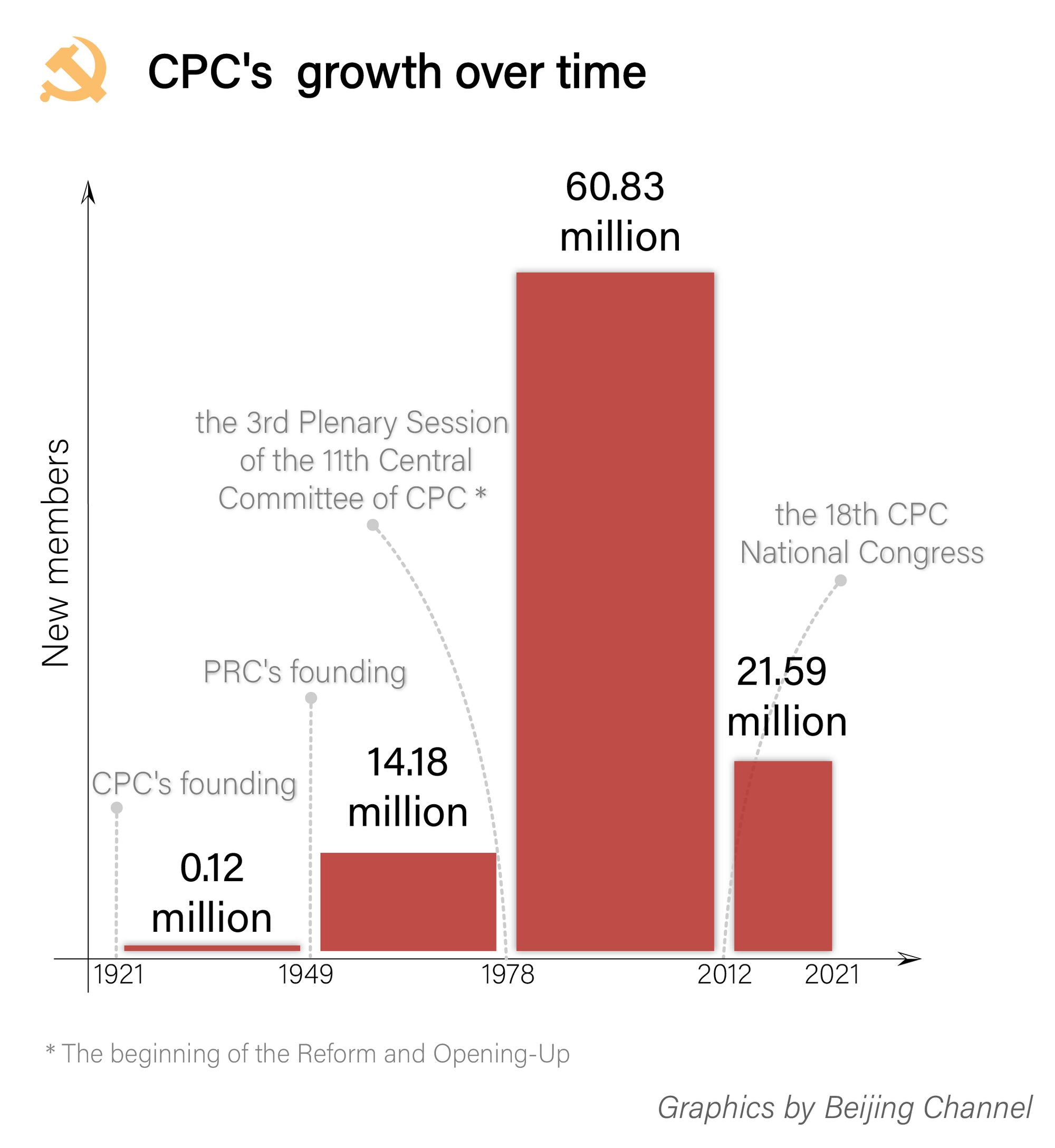

Overall the stats showed that the party had seen healthy growth in 2021, adding 3.7% new members to reach 96.7 million in total or nearly 7% of China’s population.

According to CPC application procedure, aspiring party members should tender their written applications to their local party committee. If agreed by the local CPC committee, the applicant is considered a party activist (入党积极分子). After no less than a year of evaluation by the party and attending training programs, activists would become probationary members. A probationary member has duties similar to those of full members, except that they may not vote in party elections nor stand for election. After another year of observation, a probationary member would become a full member.

The following three charts explain the composition of the party.

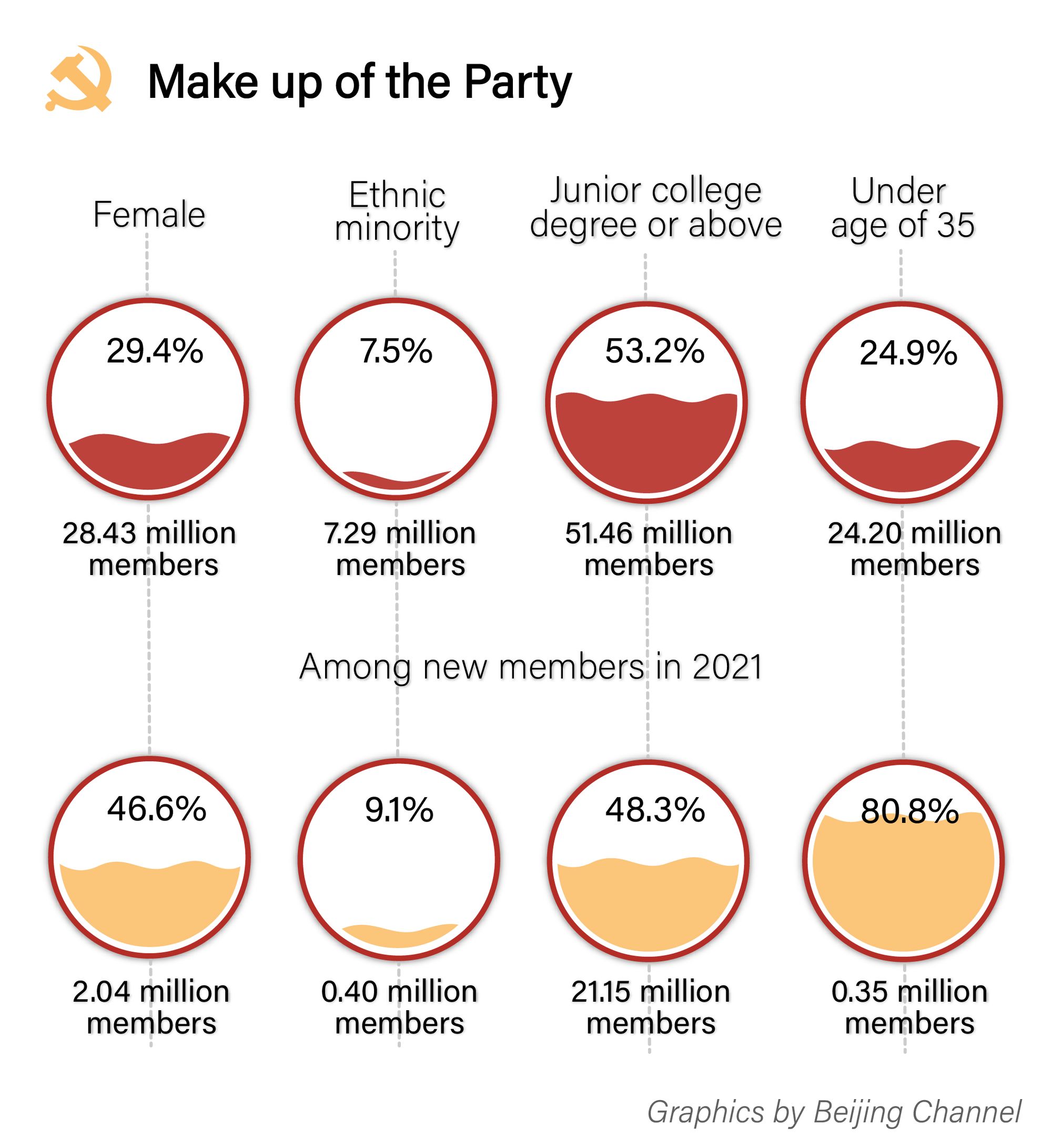

Classified by identity, women make up about 30% of party members. However, the party has made efforts to balance the gender ratio among its members in recent years, and female representation in the party has steadily risen. In 2021, nearly half of all new members are women.

According to the latest census results, the ethnic minority population (all ethnic groups other than the Han) make up about 8.89% of China’s population, which is reflected by the percentage of ethnic members in the party and among new members.

When it comes to people who’ve received higher education, the party clearly shows a preference. About half of its members and new members have a college degree, though less than 16% of the entire Chinese population do so.

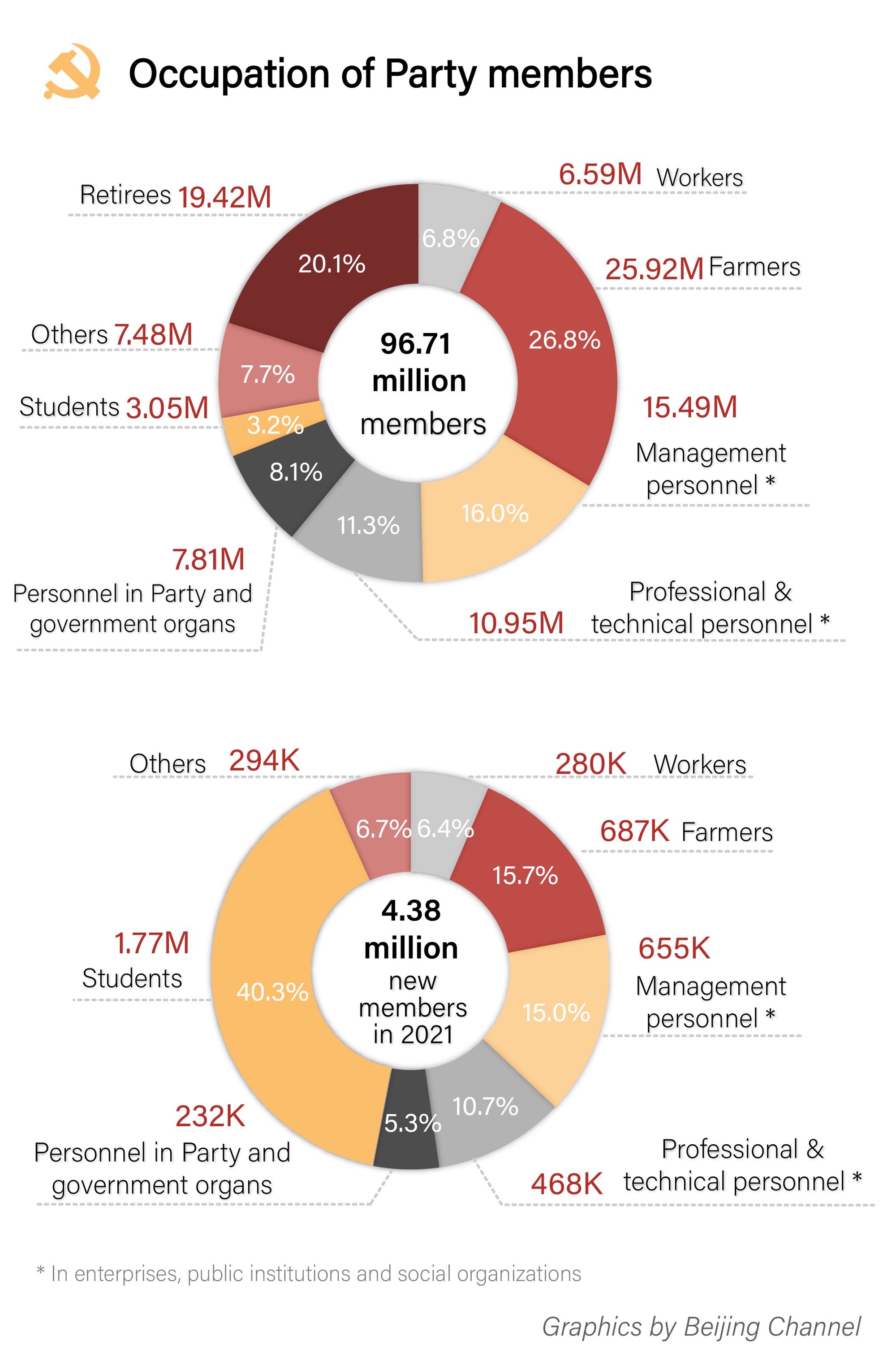

Classified by occupation, one detail worth paying attention to is the considerable gap between the percentage of farmers among party members and new members. The clue to explain this gap lies in the Chinese census.

Due to China’s rapid urbanization, its farmers, herders, and fishermen are in sharp decline. According to the Chinese census, in 2020, only 36% of the Chinese population lived in rural areas (though not everyone living in rural areas are farmers, herders or fishermen), compared with about 50% just ten years earlier. Therefore the difference between of percentage of farmers as party members and new party recruits is likely a result of China’s demographic change.

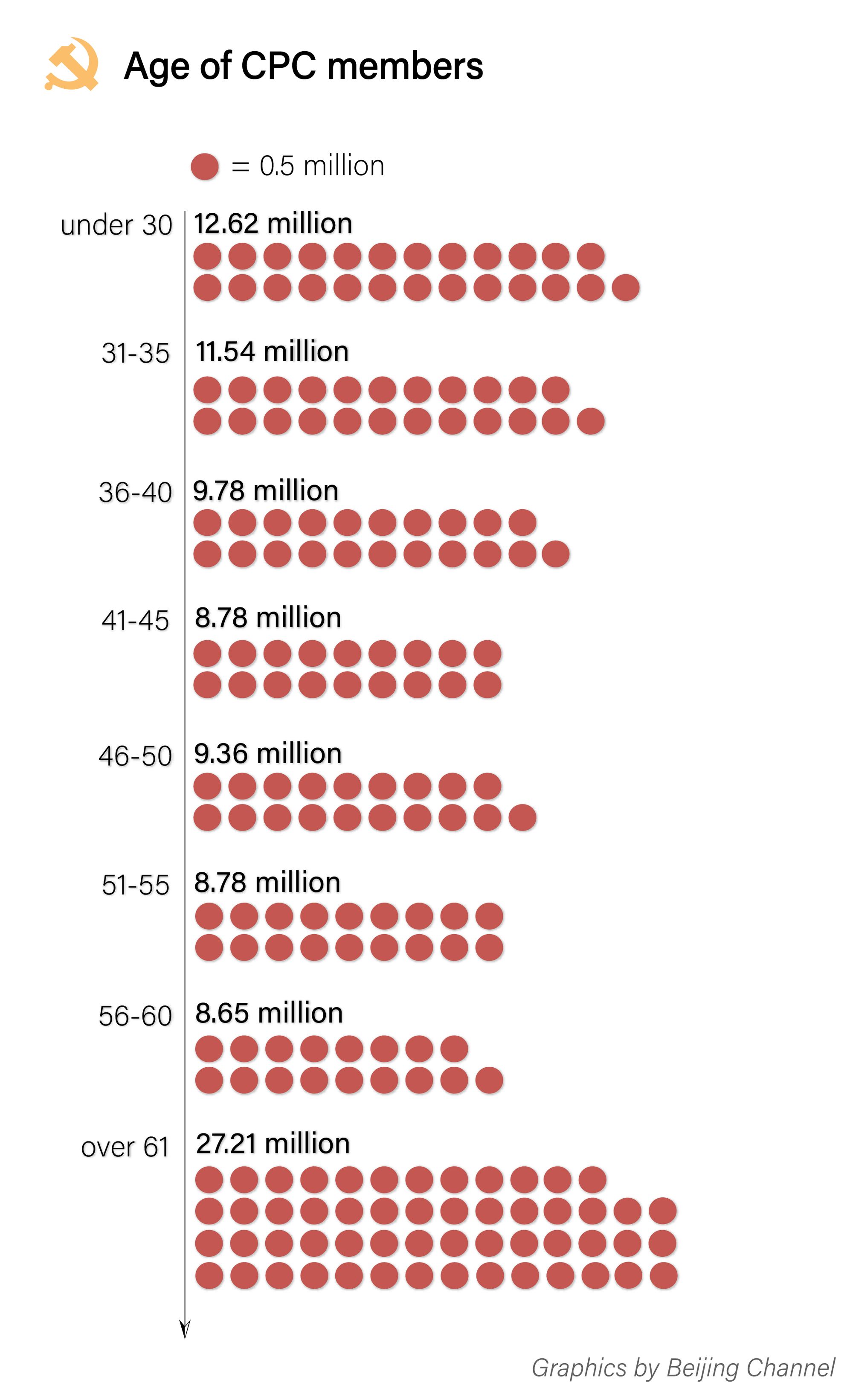

Classified by age group, the party members are distributed evenly among all age groups. But new members are predominantly below 35 (see chart 2).

Statistics also suggested that the party has been growing faster in the past decade than before. Among the four eras that are set apart by key turning points of the party, it can be seen that membership growth since the 18th party congress has been the fast among the four eras.

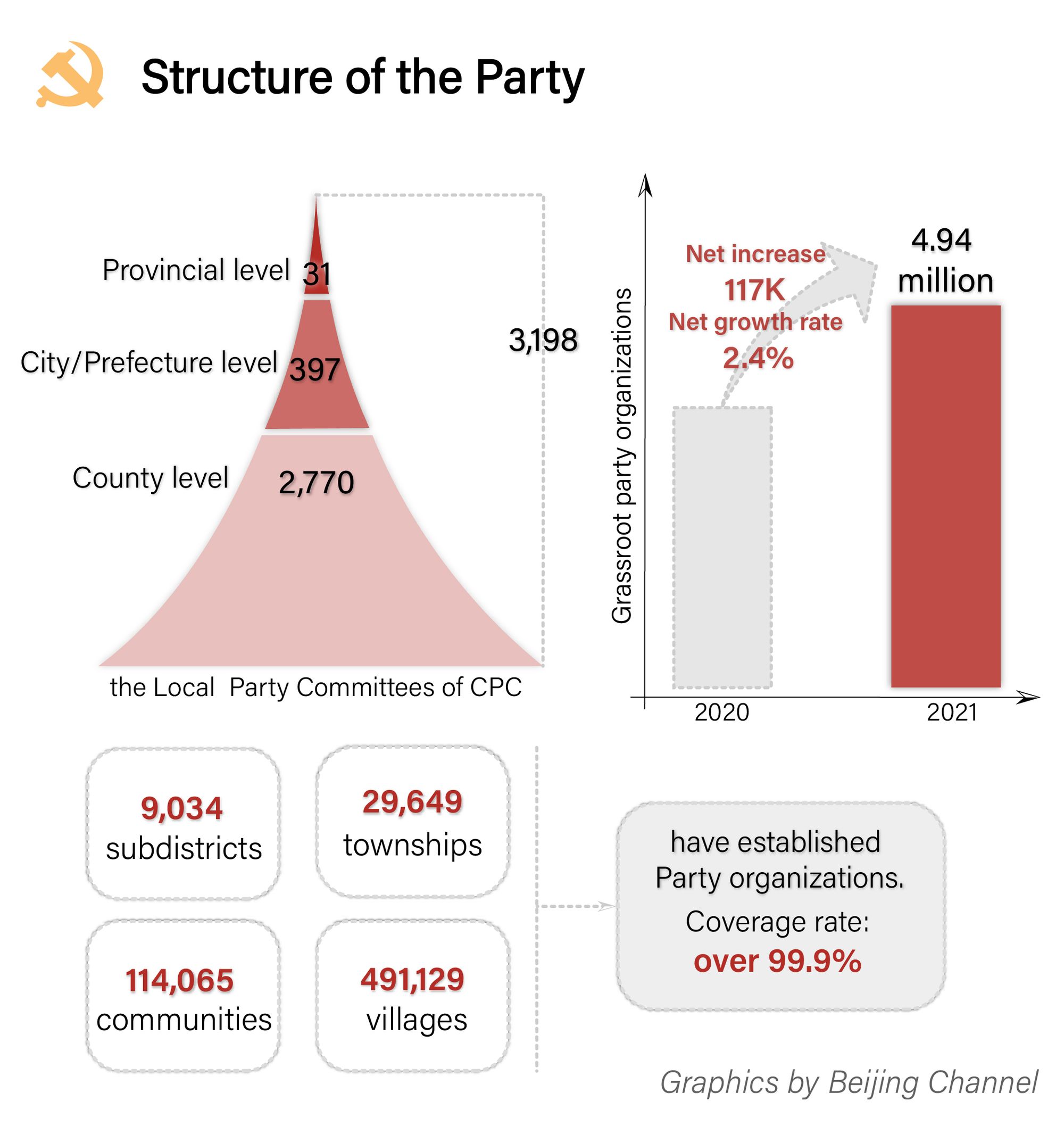

Now on CPC’s structure. Here we mainly look at the party’s regional structure and the party’s grassroots structure.

The party’s regional structure refers to party committees of administrative regions, such as provinces, cities/prefectures, and counties. When you see references in news reports of “party chief” in a particular city or province, that’s the top party official of the party’s committee of that particular administrative region, and in Chinese governance, that region’s top official.

The other dimension to observe the party’s structure is the party’s grassroots structure. According to the party charter, “In businesses, villages, governmental institutions, research institutions, communities, social organizations, PLA companies, and other grassroots organizations, there shall be a grassroots organization whenever at least three party members are present.”

In 2021, the CPC net added 117 thousand such grassroots organizations, registering a 2.4% growth. The report says grassroots organizations have been established in almost all places that warrant one.

PART 2: Puzzling Party Numbers (by Adam Ni)

I recommend Neil Thomas's June 2020 article on Party recruitment trends. It helps us put the latest data into the context with a focus on the Xi period. Data released since that article was published (the 2020 and 2021 data) highlights that the identified trends are changing. Note that the graphs I use below are from that article.

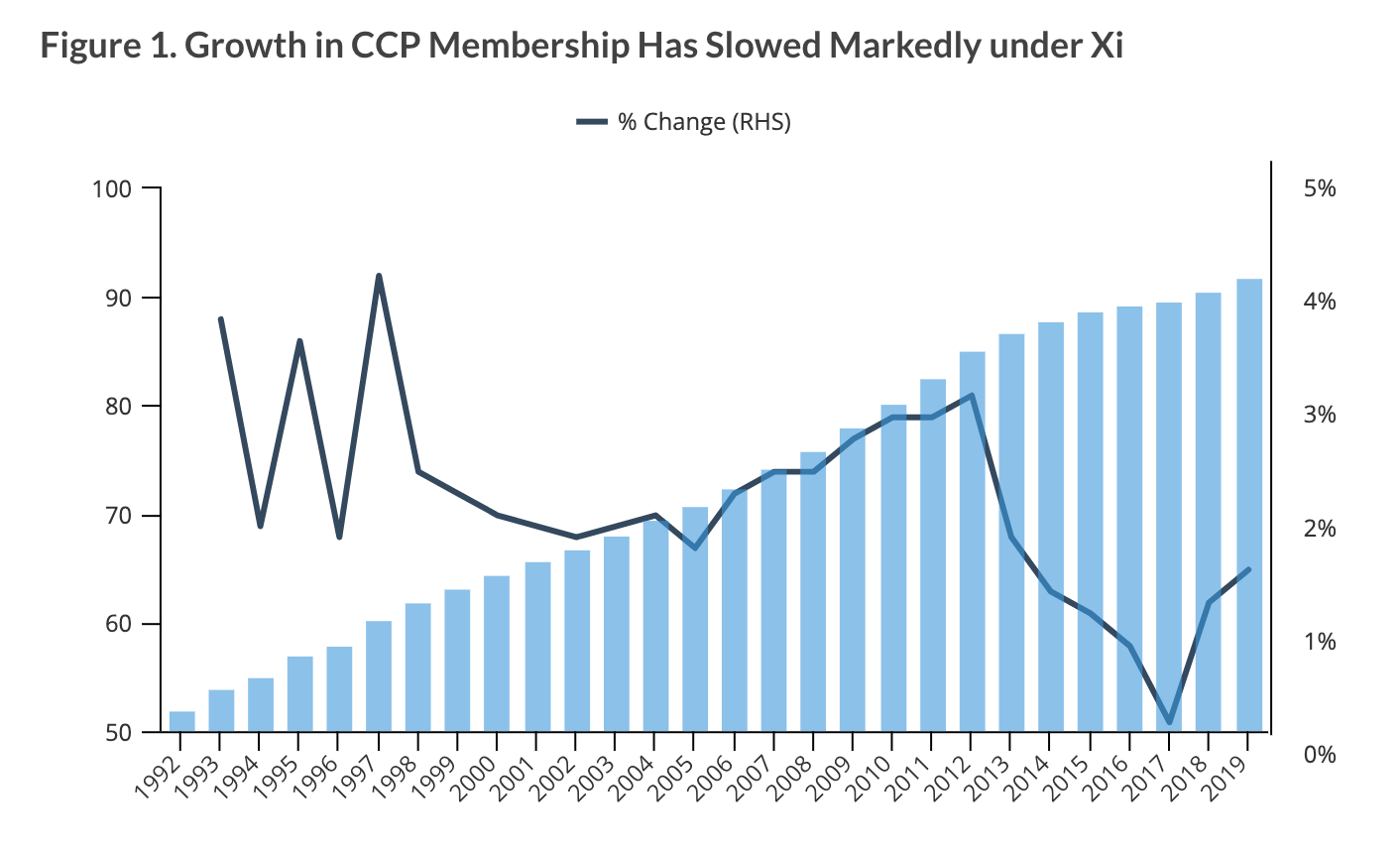

For one, Party membership growth has picked up again (3.5 and 3.7 per cent in 2020 and 2021) after dropping drastically after Xi came into power in 2012. We are now back to the 1990s and 2000s growth levels. The reason for the drop in membership growth in the period 2013 to 2019 is due to more stringent recruitment criteria ("quality over quantity").

But it's not clear why growth picked up again after 2019. One possibility is that Party leaders are increasing concerns about the Party's ageing demographics and the need to inject new blood.

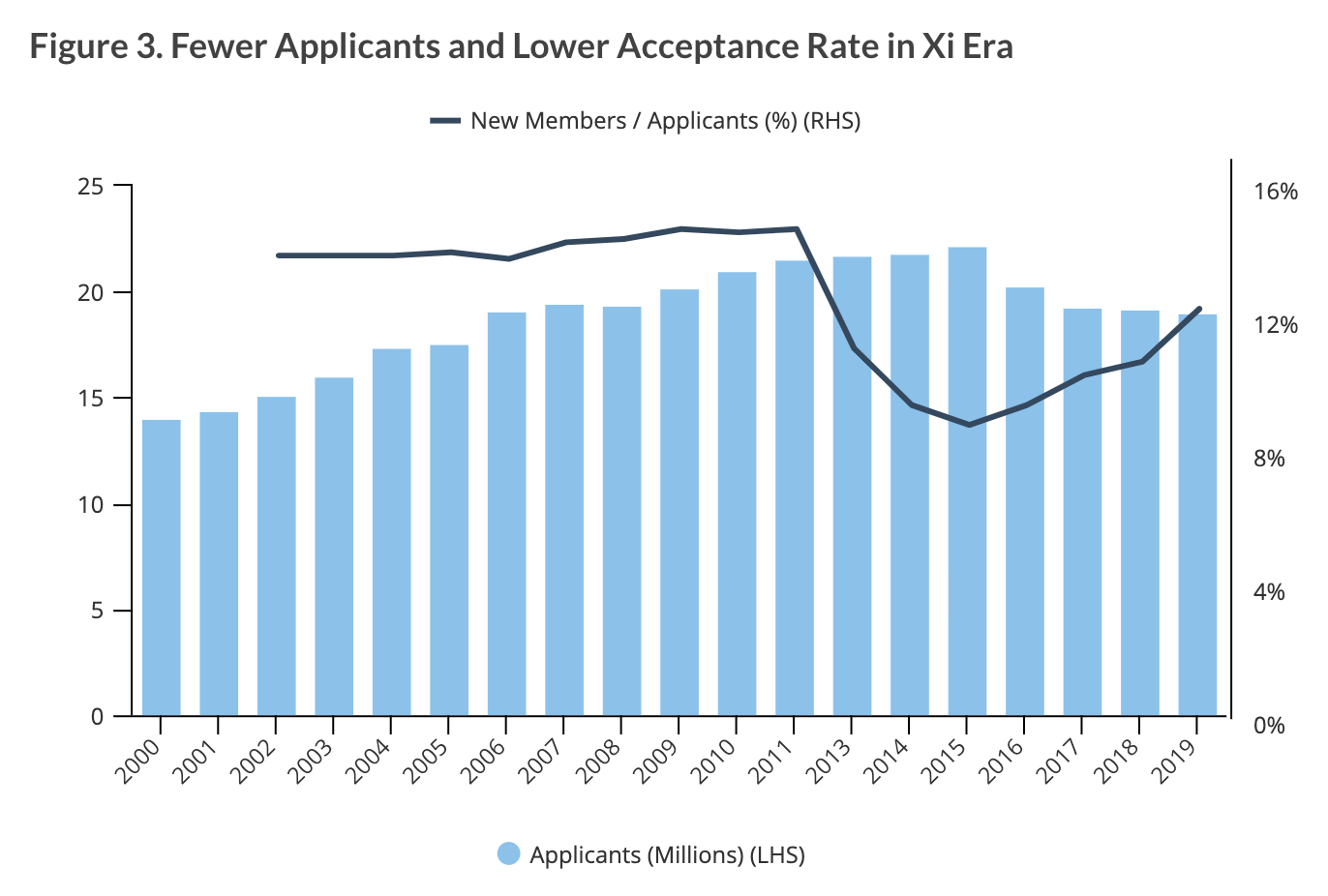

Second, the ratio of new members to new applications (a proxy for the "acceptance rate") held steady in the Hu-Wen era at around 15 per cent. This number dropped between 2012 and 2019, averaging around 10 per cent. In 2020 and 2021, the ratio has rebounded to 16 and 17 per cent, respectively.

This is perplexing given the emphasis of the Party during the Xi period on "quality over quantity" in recruitment. Has the overall quality of the candidates improved, or has the Party decided to make membership more accessible to applicants, and if the latter, then why?

Third, the Party is making steady progress on gender and minority representation. On gender, from 2012 to 2019, on average around 25 per cent of new members are women. In 2020 and 2021, the figures rose to 45 and 47 per cent respectively, indicating a deliberate effort.

The non-Han minorities' share of Party membership grew from 6.1 per cent in 1998 to 7.5 per cent in 2019 (compared to 8.9 per cent of the total population).

In recent years, the Party has emphasised the need to improve human capital by recruiting more educated candidates. The result is that the Party membership is becoming more elitist, making it harder to identify with workers and farmers (peasants). But at the same time, the Party membership is becoming more representative of the Chinese population in some areas, such as gender and minorities.