June Fourth at 35, Australian Views on China

June Fourth at 35

In April 1989, Chinese students began mass demonstrations for political reform and free speech, garnering widespread support from workers, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens. By May, one million people had gathered in Tiananmen Square. The protests shocked the Communist Party, prompting a brutal crackdown that killed hundreds, possibly thousands.

The events of 1989 are pivotal to China’s modern history. To mark the thirty-fifth anniversary, I reflect on the tension between grassroots movements and authoritarian control, the importance of historical memory, and the moral complexities of engaging with authoritarian regimes.

Grassroots Movements and Authoritarian Control

June Fourth demonstrated that mass collective action is possible under the authoritarian conditions of post-Mao China. While its legacy is contested and shaped by contemporary events, it undeniably inspired a new generation of Chinese activists. The 1989 protests also informed subsequent movements, including the 1999 Falun Gong protests, the 2018 JASIC labour movement, the 2019 Hong Kong protests, and the 2022 ‘White Paper’ protests.

The Communist Party paints Chinese society as harmonious, while some detractors depict the Chinese as an oppressed population on the brink of rebellion. The truth is more complex: grassroots movements are prevalent beneath these caricatures, as expected in a vast and diverse land like China. Activists and ordinary citizens engage in collective actions daily — feminists, environmentalists, labour activists, human rights lawyers, military veterans, and advocates of local issues continue to push for change.

The Party’s bloody response to the 1989 protests highlights the lengths authoritarian regimes may go to maintain power. Today, China’s surveillance state, internet censorship, and suppression in regions like Xinjiang and Hong Kong are lived realities for millions, serving as poignant reminders of the tension between grassroots power and authoritarian control.

Historical Memory

Among the spectres haunting China is June Fourth.

The Communist Party refers to the 1989 protests as the ‘June Fourth Incident,’ portraying them as unrest instigated by agitators and foreign elements. The Party justified the violent suppression as necessary to restore order and prevent chaos. With the traumas of the Cultural Revolution still fresh, many Chinese accepted this justification, though many questioned the necessity of such brutality.

Official history portrays the 1989 events and their aftermath as a brief interruption in the nation’s progress during the reform era; Deng Xiaoping would reignite China’s economic ascent with his 1992 Southern Tour. They say this is history.

The Party’s efforts to erase June Fourth from collective memory reflect a broader strategy to control historical narratives. Like previous rulers of China, the Party systematically rewrites history to legitimise its existence and policies, both past and present, thereby limiting our vision of China’s future.

Two recent books reinforce the notion that we should be sceptical of the Communist Party’s accounts of the past and, more broadly, adopt a critical mindset towards conventional narratives of Chinese history and assumptions about China today.

In “Never Turn Back: China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s,” Julian Gewirtz traces elite debates in the decade leading up to the tragedy of June Fourth. Gewirtz reveals that the Party’s narrative of internal cohesion and a grand plan is a misleading caricature of much more contingent and contested processes that could have led China to greater openness and political reform.

In “Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and their Battle for the Future,” Ian Johnson explores how underground historians strive to preserve memories of events like June Fourth and other suppressed histories. Johnson reflects on whether amnesia will prevail, concluding that ongoing struggles shape collective memory, making the fight for historical truth an enduring process.

Fundamentally, the search for truth and acts of remembrance are essential as they define us, offer lessons from the past, and safeguard against distortions and amnesia.

Dealing with Authoritarians

The Beijing massacre led to widespread international condemnation and strained relations between China and Western countries. The United States, the European Union, and several other countries imposed sanctions on Beijing, including arms embargoes, some of which remain in effect today.

Over time, economic interests took precedence, and relations thawed and flourished.

This history is relevant today as we consider how to respond to Beijing’s Xinjiang and Hong Kong policies. Non-engagement is costly and often impractical due to material interests and global challenges. But at what point do we become complicit in human rights violations? Foreign governments and companies are, or at least should be, grappling with these questions.

Engaging with authoritarian regimes requires balancing ethics with pragmatism. Instead of viewing the world through a prism of moral absolutes and untested assumptions, each situation should be assessed individually.

Ultimately, there are no simple or comfortable answers.

Australian Views on China

Lowy Poll 2024

Since 2017, relations between Australia and China have deteriorated significantly, reaching their lowest point in decades by 2021/2022 at the peak of political tensions. Over the past two years, the relationship between Beijing and Canberra has been thawing, culminating in mutual visits by leaders: the Australian Prime Minister visited China in November 2023, and the Chinese Premier visited Australia in June 2024.

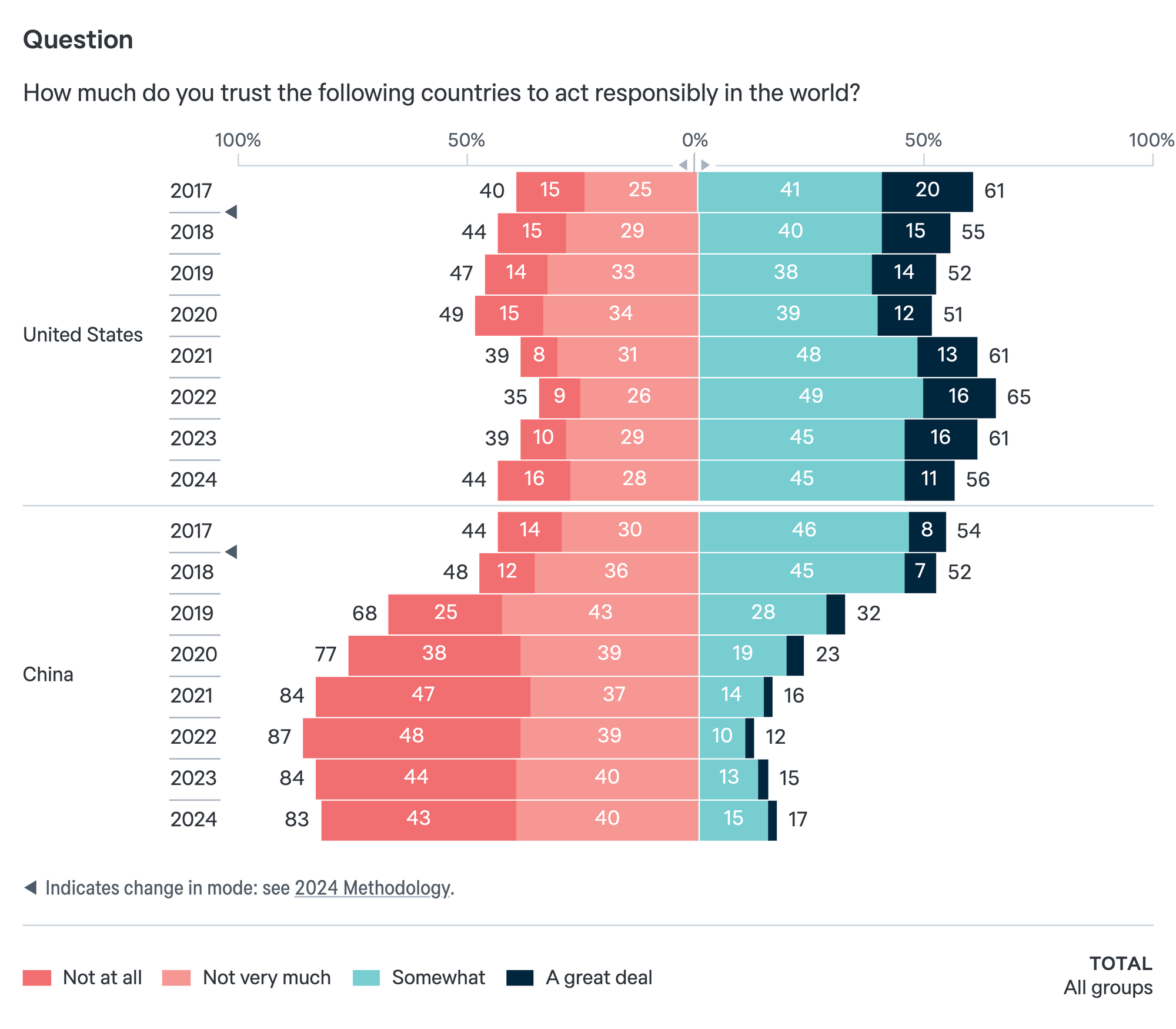

The 2024 Lowy Institute Poll underscores the decline in Australian public sentiment towards China. Despite slightly less negativity in this year’s results, Australians remain deeply distrustful of Beijing. They are increasingly concerned about Australia’s security in light of China’s military ambitions.

Deep Distrust

83 per cent of Australians surveyed do not trust Beijing to act responsibly. Despite low levels of trust, Australians are divided on the state of the bilateral relationship, with 47 per cent viewing it as “quite bad” and 43 per cent viewing it as “quite good.”

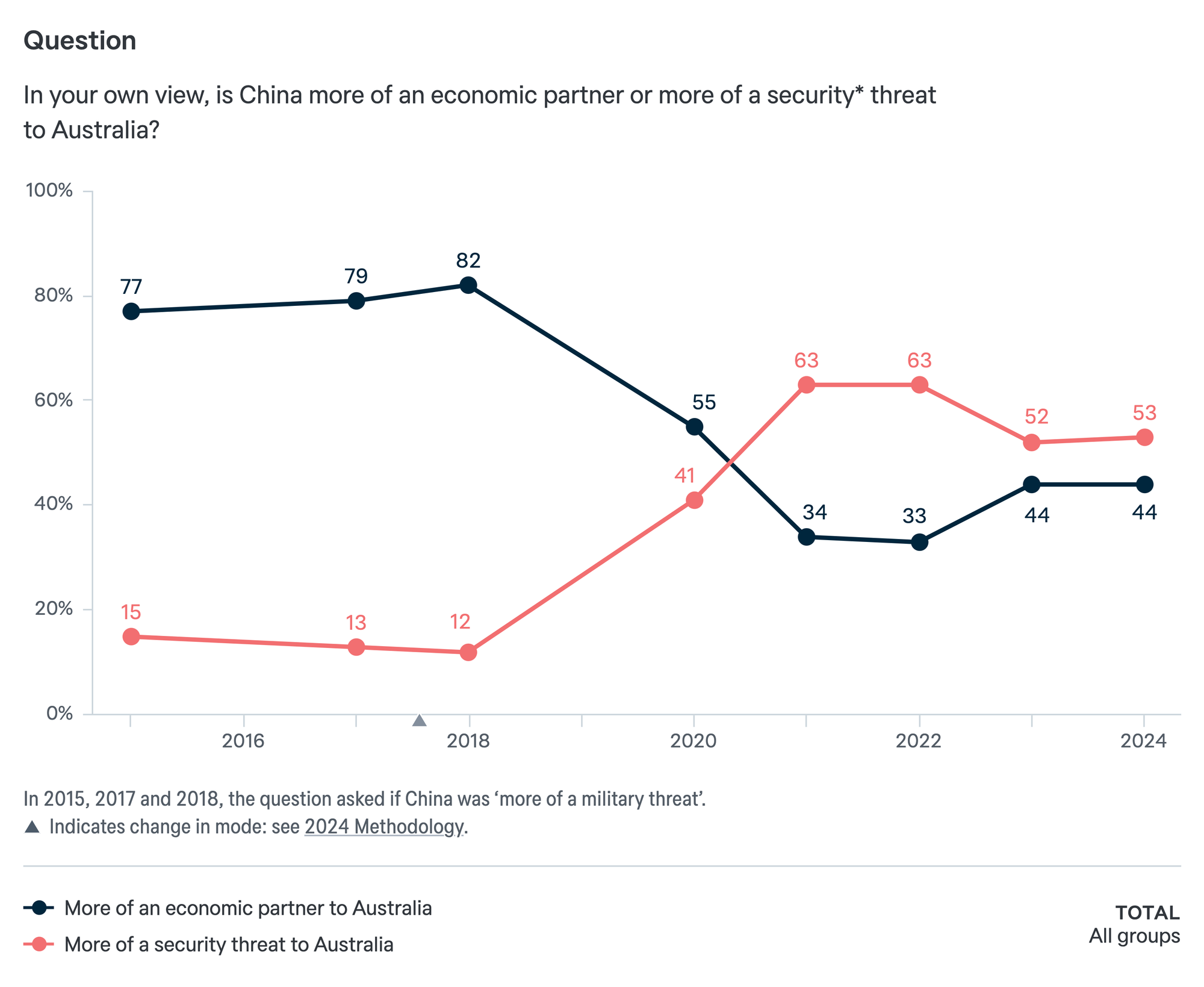

Opportunity vs. Threat

Until 2020, Australians viewed China more as an economic partner than a security threat. This flipped in 2021, during the peak of political tensions, with 63 per cent seeing China as a security threat and only 34 per cent as an economic partner.

By 2024, public sentiment had moderated, with 53 per cent viewing China as a security threat and 44 per cent as an economic partner.

Most Australians (71 per cent) believe China will likely become a military threat in the next 20 years. This is a slight decrease from the 75 per cent who held this view in 2023 but still significantly higher than the 45 per cent who held this view in 2018.

Security and Geopolitics

Successive Australian governments have pursued a defence strategy focusing on deterring China, strengthening ties with the United States, and expanding defence cooperation with other countries.

Australia’s alliance with the United States is considered crucial yet potentially risky: 63 per cent believe it protects Australia from China; 75 per cent worry it could draw Australia into conflicts in Asia.

Japan is favoured as a close security partner, reflecting a desire to strengthen ties with “like-minded” countries. Public support for defence measures like acquiring nuclear-powered submarines under the Australia–United Kingdom–United States (AUKUS) partnership remains strong.

Along with deterrence, the current Labor government emphasises improving the relationship with China through cooperation. Both deterrence and reassurance find support among the Australian public, with 51 per cent prioritising stability over deterrence and 45 per cent prioritising deterring China.

Thoughts

First, Australian politicians and commentators often lack clarity in defining the country’s core interests and critical concepts, such as the rules-based order. This vagueness comes from a lack of thoughtfulness or an unwillingness to examine complex issues critically. For instance, security and economic interests are sometimes viewed as mutually exclusive, overlooking the crucial role that economic stability plays in ensuring Australia’s national security.

Second, the “China threat” narrative often exaggerates risks, leading to overreactions like eroding civil liberties under the guise of protecting against espionage and unfairly questioning the loyalty of Chinese Australians. Additionally, Canberra sometimes treats Beijing differently from “like-minded” countries like India, Israel, and the United States on issues that demand consistency, such as human rights. While avoiding whataboutism is important, Beijing’s actions should be assessed within a broader international context.

Third, China has increasingly become a convenient justification in Australian politics, including to justify policies ranging from industrial support to military procurement. Politicians find it easier to point the finger at Beijing than to explain the deeper, more complex causes of Australia’s challenges to the public.

Finally, viewing China solely as an economic opportunity or a security threat is reckless. China is a diverse and complex nation, home to one-sixth of humanity. A deeper understanding of China enriches our perspective and affirms our shared humanity beyond mere practical considerations.