Brief #91: climate, history, Digicel, news sources, Li Yundi

1. Climate policy

The Chinese Government is getting very serious about climate change. A few days ago (just before the Glasgow Climate Change Conference), the Central Committee and the State Council jointly released Working Guidance For Carbon Dioxide Peaking And Carbon Neutrality In Full And Faithful Implementation Of The New Development Philosophy 关于完整准确全面贯彻新发展理念做好碳达峰碳中和工作的意见 [English | Chinese].

As Xi is not attending the climate conference, this can be read as China’s action and response to the global challenge of climate change.

Commitments

From the start, to underscore the importance of the issue, the document emphasised that achieving peak carbon emissions 碳达峰 and carbon neutrality 碳中和 is a “major strategic decision” 重大战略决策. The domestic justification is that it is necessary to achieve “sustained development of the Chinese nation”, 实现中华民族永续发展, thus linking carbon policy to national rejuvenation. So it would be inconceivable for people in China, including local officials, to go against the major strategic decision that affects the sustainability of the Chinese nation.

The document sets out concrete qualitative and quantitative targets, including (but not limited to):

By 2025:

- Energy consumption per GDP will be 13.5% lower than 2020 level

- Carbon emissions per GDP will be 18% lower than 2020 level

- Non-fossil energy consumption will reach around 20%

By 2030:

- Energy efficiency in key energy-consuming industries will reach advanced international levels

- Carbon emissions per GDP will drop by more than 65% compared with 2005 level

- Non-fossil energy consumption will reach around 25%

By 2060:

- Energy efficiency will be at the advanced international level

- Non-fossil energy consumption will be over 80%

- Successfully achieve carbon neutral

The document is far-reaching — it affects numerous policy areas including investment, financing, and tax; and it covers industrial restructuring, energy industry, transportation industry, rural development, and research and technology industries.

To demonstrate commitment, the document also highlights oversight and performance assessments 监督考核. For example, it is explicit that all local authorities must build targets for carbon peaking and neutrality, and that performance assessment is to be strengthened, including that “outstanding regions, organizations, and individuals to be duly rewarded and commended and regions and departments that fail to accomplish their goals and tasks to be criticised”. This should be a strong incentive for local authorities to ensure their carbon targets are achieved. It may even lead to over-achievement at the expense of other priorities.

In contrast to what people may have expected from recent power shortage, the Government is strengthening dual-controls over energy intensity and gross energy consumption 能源消费强度和总量双控, and this includes stepping up supervision and law enforcement 监察和执法. Regions in danger of missing targets will face delay or restrictions of project approvals 缓批限批.

Specific industries

The document outlines restrictions to be placed on energy-intensive and high-emission industries 高耗能高排放 as well as inducements to developing green and low-carbon industries 绿色低碳产业. The Government has committed to strictly controlling investment in high-carbon products while increasing support for energy conservation projects. The sector-by-sector intervention is one of the heavier state directions.

For example, authorities will continue to conduct “look back” inspection of steel and coal overcapacity 钢铁煤炭去产能“回头看”, in order to prevent overcapacity from phenoxing. For industries such as steel and cement, capacity substitutions will be implemented at equal or reduced levels. And oil refinery operations, unless listed in national industrial plans, are prohibited from new construction or expansion.

For the power generation sector, the document has indicated that China will look to more market-based solutions 市场化改革 to improve the national unified energy market 能源统一市场. The fragmentation of regional markets was one of the reasons for the recent power shortages. The document has also banned the practice of giving preferential electricity pricing to energy-intensive and emission-intensive industries.

On the other hand, China will focus on developing “strategic emerging industries” 战略性新兴产业, which includes next-generation information technology, biotechnology, new energy, new materials, high-end equipment, new energy vehicles, environmental protection, aerospace, and marine equipment. However, China is facing increasing international concerns and resistance regarding its progress in these emerging technology industries.

International dimension

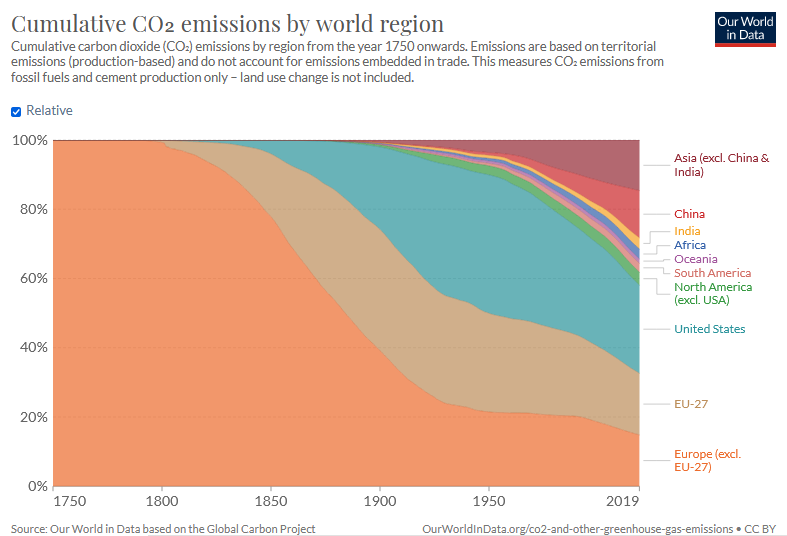

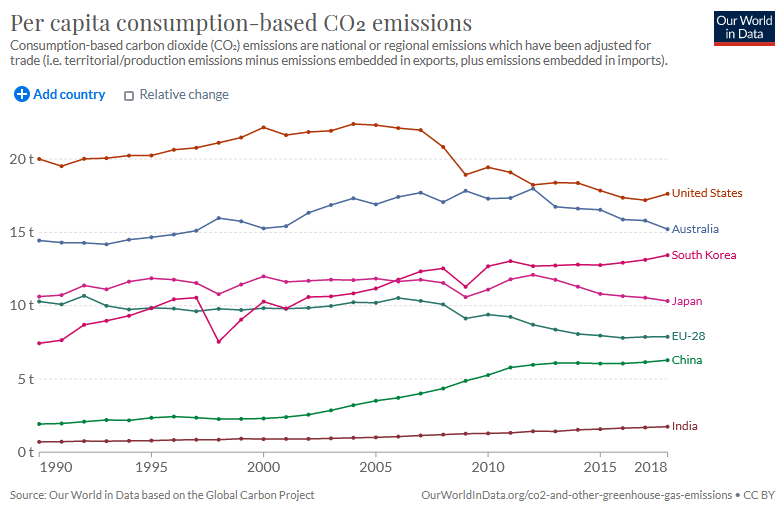

China is still eager to remind other countries of its developing country status, hence its adherence to the principles of common but differentiated responsibilities 共同但有区别的责任. This means other countries should not expect China to share the global burden as a developed economy.

On trade, China has committed to regulating exports of energy-intensive and high-emission products and expanding imports of green and low-carbon products. Historically, as the world’s factory, much of the exports was in highly-polluting industries that developed countries did not produce themselves. Restrict exporting energy-intensive industries requires a restructuring of the economy, which China is looking to do.

However, internationally, this means that China will increasingly compete with developed economies rather than complement their economies. Over time, trade may become less of ballast to tension in political relationships.

On foreign investment, China will strive to make green the defining colour of BRI 让绿色成为共建“一带一路”的底色. As a major financier of infrastructure internationally, this has the potential to significantly reduce global emissions if implemented strictly.

2. History in the making

Last week, the Politburo examined the issue of comprehensively summarising the major achievements and historical experience of the Party’s century of struggle. (Adam’s translation of the meeting outcome here). The draft resolution will be submitted to the Central Committee in November.

As we have emphasised repeatedly, history is important for the CCP. A verdict on history does not only impact how history is narrated and taught but also the future trajectory of the country. Xi has been active in cracking down on so-called “historical nihilism”. So the resolution on history is a big deal, and it has only been done twice before — once in 1945 before the establishment of PRC and once under Deng in 1981, which passed a verdict on the Cultural Revolution.

Just as an illustrative example, the official China Internet Rumour Refuting Platform was launched in July targetting rumours that “smear party history”, including “revolutionary leaders, heroic figures and historical events”.

Among the “top 10 rumours” to be combatted include:

- Mao is not the real author of a poem

- Mao’s son was exposed and subsequently killed in the Korean War because he was making egg fried rice

- Lei Feng’s diary is fake

- The CCP did not fight against Japan

- Land reform was wrong and the landlords were actually nice people

- The USA did not plan to attack China during the Korean War

We are against this kind of state enforcement of historical narrative, so we are proudly “historical nihilists”.

Yet, some jurisdictions in liberal democracies are also going down this road well-trodden by the CCP. This mostly manifests in how history is taught in schools. For example, Texas, a place I lived for a year, has banned the teaching of “critical race theory” — they may as well branded it “historical nihilism” — and has legislated to promote “patriotic education” (no need for a name change here).

In Australia, the federal Minister for Education has criticised the history curriculum. He said the curriculum “has a negative view of our history” and “downplayed our Western heritage”. Instead, he seems to want to instil patriotic education with positive energy: “Ultimately, students should leave school with a love of country and a sense of optimism and hope that we live in the greatest country on earth”.

What the Australian Minister of Education proposes is basically what the CCP has done… instilling/indoctrinating a love for the country so that future generations will “defend it as previous generations did”.

There are more similarities between some right-wing parties in liberal democracies and the left-wing CCP than meets the eye.

3. Digicel

Speaking of Australia imitating China… Back in July, I wrote:

Australian taxpayers may end up funding the purchase of Digicel Pacific, a telecommunications company servicing the Pacific and owned by an Irish billionaire. The reason behind the taxpayer funding is all about China — concerns that China might buy it.

Now the Australian Government has announced that the taxpayers will be helping Telstra, a private Australian company, to acquire Digicel from the Irish billionaire.

The Australian Government said this “enables Telstra to take this commercial opportunity”. Of course, this deal is not purely commercial — if it was, then Telstra would not need help from the government. Instead, the deal is more importantly part of “Australia’s longstanding commitment to growing quality investment in regional infrastructure”.

From an aid effectiveness’s point of view, the question is whether this is the most effective and efficient way to help the Pacific countries? On this, Stephen Howes is sceptical:

Many will welcome the investment as a sign of Australian commitment to the Pacific. However, if we want to invest in the telecom sector in the Pacific, we should be backing alternatives to Digicel, to push prices down and improve services, not buying out the dominant player. [...]

The Australian government also needs to decide if its only goal is to counter China or if it still seeks to promote Pacific development.

This sort of government-private partnership to fund overseas acquisition is quite normal for China. The Chinese Government often directs Chinese companies (mostly state-owned enterprises) to invest in particular projects, sometimes for geopolitical reasons.

But as Shahar Hameiri noted,

The Telstra decision is the clearest indication yet that Australia’s hand-off approach to its firms’ activities abroad is being supplanted by more active direction of outbound investment and development financing.

For me, this appears to be another case where Australia is concerned about China’s actions (government supporting foreign acquisitions), and counter this by doing exactly what China has done.

4. Approved news

The Cyberspace Administration of China updated its list of approved “internet news source” 互联网新闻信息稿源单位名单. Only news sources on the list can be republished by internet platforms. The current list contains 1358 news sources.

The focus of the update notice is on “positive energy”. That is, the regulator wants internet news sources to promote positive news about the country and the party. The update added news sources that were politically correct 政治方向 and removed news sources that had “poor day-to-day performance” 日常表现不佳.

Most notably, Caixin 财新, China’s best known non-government news source, was removed from the list. Among other “non-positive” news it published was its investigation on COVID death numbers in Wuhan in March 2020.

Removing Caixin from the list means internet platforms cannot re-publish content from Caixin. Normally this can significantly reduce the influence of the news outlet, as many readers get news through aggregators rather than go to the source directly. However, in Caixin’s case, it has been behind a paywall since 2017, which means readers would have to go to the source directly anyway.

Overall, this development is another sign that the party-state is tightening control on information in the country. It is strengthening its “guidance” to ensure only positive news about the party is reported.

So for readers of news from China, we may have to be even more sceptical and critical about the framing of most news stories.

5. Li Yundi

Social media in China exploded this week with the news that the famous pianist Li Yundi 李云迪 has been detained for soliciting a prostitute. Li is a “celebrity” on the level of a pop star, despite being a concert pianist.

As regular readers of Neican know, the Chinese Government and the Communist Party is cracking down on celebrities recently. And one target of the crackdown is “immoral” (not just illegal) behaviours of celebrities. In this case, prostitution and soliciting prostitution are both illegal (along with pornography) in China. However, prostitution is still rampant in China, and most do not get into serious trouble for it.

On social media, the platforms have allowed some comments questioning his detention, with many criticising the lack of privacy afforded to him and disputing whether punishment should be imposed for prostitution in the first place. Speculations are also rife as to why he was targeted, as one would expect many celebrities to engage in similar acts.

Despite prostitution being a relatively minor crime (around two weeks in detention), Li’s career has been destroyed by this revelation.

Neican Brief is supported by the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University.